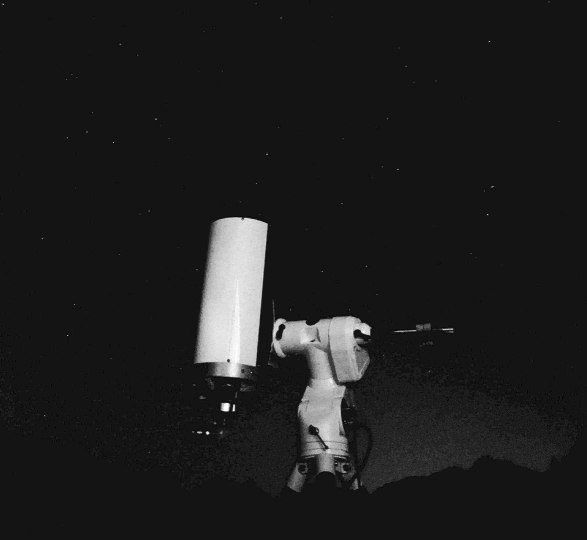

VIXEN VC200L "VISAC"

Anno 2017

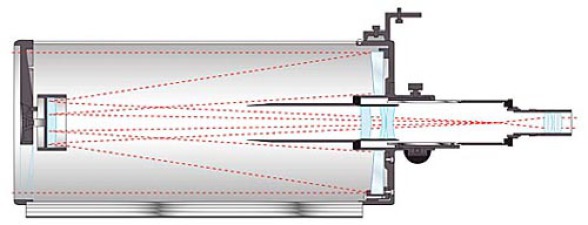

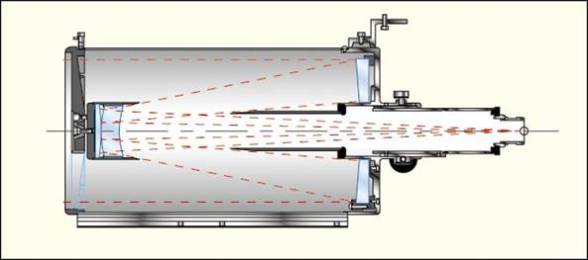

INTRODUZIONE E ACQUISTO

Il VISAC è in produzione da oltre vent’anni quindi ritengo superfluo entrare subito nel merito di “cosa sia” (per questo rimando alla sezione successiva dell'articolo che riporta quanto già scritto quattro anni fa a proposito). Affinché però anche i lettori meno smaliziati possano avere una vaga idea del progetto Vixen (VISAC è un acronimo che sottende le parole Vixen's Six-Order Aspherical Cassegrain) posso ricordare che si tratta di un derivato del cassegrain con un correttore spianatore a tre elementi posto poco prima del punto di fuoco e alloggiato nel canotto dello specchio primario.

Il progetto appartiene alla Vixen ed ha molte frecce nel suo arco benché lo strumento non abbia ottenuto il successo meritato, almeno al suo esordio.

I vantaggi della soluzione Vixen rispetto ai classici compound di pari apertura come gli Schmidt-Cassegrain tradizionali sono molti e non vanno sottovalutati.

Innanzitutto il tubo ottico è aperto e garantisce non solo un acclimamento delle ottiche molto veloce rispetto ad un sistema chiuso ma anche risolve il fastidioso problema della condensa sulla lastra correttrice anteriore.

Il sistema di focheggiatura avviene con un tradizionale pignone e cremagliera di buona fattura e diametro da 60 millimetri, e se a questo si aggiunge che lo specchio primario è fisso (benché collimabile) si comprende quanto il sistema non risenta di tilt involontari della massa vetrosa o di "focus shift".

Altro aspetto determinante è rappresentato da un campo di piena illuminazione da 40 millimetri e una planarità e correzione del campo inquadrato quasi completa (e notevolmente superiore a quella di un sistema Schmidt-Cassegrain).

Dulcis in fundo, il progetto Vixen prevede la possibilità di collimare non solo lo specchio primario e secondario ma anche il focheggiatore con una lungimiranza progettuale non da poco se pensiamo che stiamo considerando uno strumento amatoriale da 20 cm. itinerante.

Le accortezze che ho brevemente elencato, alle quali va aggiunto il rapporto focale nativo di F9 che è possibile ridurre a 6,4 con l’apposito gruppo ottico aggiuntivo, rendono bene l’idea della vocazione soprattutto fotografica e di osservazione del cielo profondo di questo “middle size” Vixen.

I rovesci della medaglia sono principalmente legati alla forte ostruzione finale e alla necessità di strutturare in modo solido i supporti della cella porta secondario.

La misura di quest’ultimo e lo spessore non indifferente delle raggiere di supporto portano l’ostruzione complessiva a circa il 44% con un conseguente aumento della luce focalizzata nel primo e secondo anello di diffrazione.

Benché un simile valore rappresenti uno spauracchio per la maggioranza degli astrofili da forum vorrei ricordare che, se da un lato è vero che una forte ostruzione si concretizza in una certa perdita di contrasto è altrettanto vero che in un sistema ottico “bilanciato” ciò che conta soprattutto sono la lavorazione ottica e la meccanica atta a farla rendere al meglio.

Quando queste sono di ottimo livello il fattore ostruzione passa in secondo piano tanto che il VISAC offre prestazioni planetarie assolutamente in linea con quelle esibite dai ottimi SC commerciali di pari apertura.

Personalmente è questa per me la seconda esperienza con il Cassegrain giapponese che ho già avuto il piacere di possedere tantissimi anni fa, quando ero decisamente più giovane e inesperto.

Nel pubblicare gli annunci di ricerca mi è stato più volte proposto il VMC (200/1950) che ha schema ottico diverso e che continua ad essere confuso con il VC200L per via di un aspetto molto simile e di caratteristiche di apertura e focale comparabili.

Per ragioni sentimentali ma soprattutto per l’utilizzo che volevo farne ero invece alla ricerca proprio del VC200L e ASSOLUTAMENTE nella sua versione originale con culatta “verdino Vixen” anche perché, estetica a parte, rispetto alla versione attualmente in commercio non è cambiato nulla né dal punto di vista meccanico né da quello ottico. Su questo aspetto vorrei essere particolarmente franco affinché si smetta di speculare sulle "versioni". Se si escludono alcune finiture estetiche (tra l'altro di opinabile valore) lo strumento nato nella metà degli anni '90 è rimasto invariato anche per quanto riguarda i coatings degli specchi. Stabilito questo va detto che il VISAC possiede un particolare tipo di coating il cui "segreto" è di proprietà Vixen e che ha importante influenza sulla correzione dello specchio e sulla sua curvatura speciale (Six-Order Aspherical).

Poiché le offerte pervenute sul terreno nazionale per uno strumento usato in buono stato erano fuori budget mi sono rivolto ai lidi natali dello strumento e ho avuto fortuna. Il bel Vixen è giunto tra le mie braccia per una prima sistemazione cosmetica e poi ottica così da potersi sdebitare con visioni spettacolari delle regioni stellari della Via Lattea.

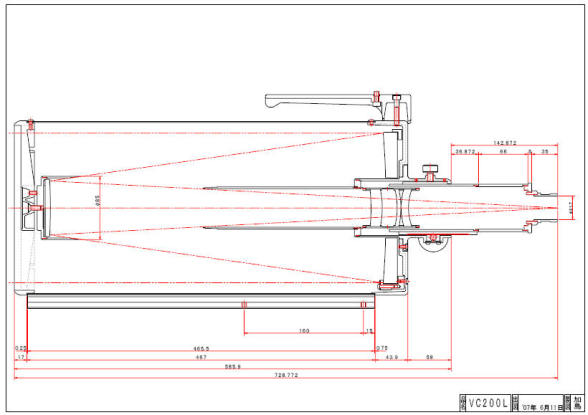

Schema ottico del “nostro” Vixen VC200L.

UNA ESPERIENZA DI OLTRE 20 ANNI FA...

Quando il sito DARK STAR è nato ha raccolto, tra le altre fonti, anche i miei appunti sparsi scritti nell'arco di quasi venticinque anni di osservazione ed esperienza). Tra questi figuravano alcune osservazioni effettuate con uno dei primi VISAC circolanti quando ero ancora poco più di un ragazzo. Per offrire maggiore completezza al presente articolo le riporto in modo completo. Si tenga presente che l'esperienza di allora era inferiore a quella odierna e anche la capacità di valutare gli strumenti.

Lo strumento mi accompagnò in ottime osservazioni del cielo, aiutandomi tra l’altro ad apprezzare l’importanza dell’ostruzione nei sistemi Cassegrain e derivati e cominciando a comprenderne l’importanza nelle visioni ad alta risoluzione, nonché gli effetti compositi a quelli della turbolenza atmosferica sulle immagini a fuoco.

Ricordo, oltre ai campi stellari da quote elevate e tipicamente intorno ai 2000 metri di altezza, alcune osservazioni di Luna e pianeti da Milano.

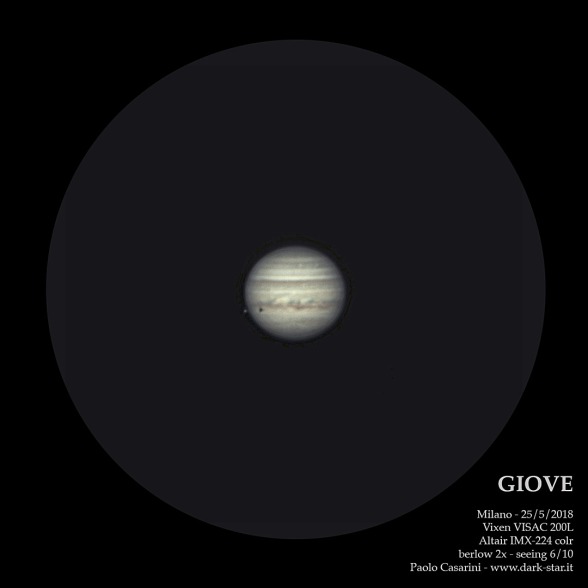

In particolar modo ritengo utile riportare un appunto dell'epoca inerente l'osservazione di un buon Giove, alto sull’orizzonte e con condizioni di stabilità termica raggiunte.

“Il pianeta raggiunge il suo massimo a circa 200 ingrandimenti - oculare da 9mm. ortoscopico Vixen. I dettagli sul globo sono paragonabili a quelli offerti da un catadiottrico di tipo Schmidt Cassegrain nelle medesime condizioni, solamente appaiono un poco più “flou” e il cielo intorno al pianeta presenta un alone di luce diffusa discreto ma ben presente. Ho la sensazione che la resa dei bianchi sia lievemente più morbida che nel rifrattore da 10 cm. sempre di casa Vixen anche se la differente raccolta della luce può suggerire valutazioni errate. Ben delineate le bande equatoriali e anche ben visibili un paio di festoni di colore freddo, tipicamente blu-grigio, che appaiono più densi che non nel 4 pollici acromatico. Risultano invece meno definite le bande polari che nel VISAC appaiono un tutt’uno o quasi mentre nel rifrattore sono più sottili e meglio separate (2 in totale nella regione nord). Altra differenza sostanziale tra i due strumenti è la immediata pulizia di immagine offerta dal rifrattore. Il bordo planetario, anche se presente una leggera aberrazione cromatica, è più netto e il cielo intorno più scuro e con minor luce diffusa. Soprattutto, nel rifrattore mancano le 4 "autostrade" di luce che corrispondono agli spikes introdotti dalla crociera del Casserain. Tali “baffi” sono larghi quanto il pianeta stesso e se nell’osservazione delle stelle possono anche essere piacevoli tendono a disturbare non poco nella visione di Giove.”

Gli appunti continuano con un test del VISAC in combinazione con una delle prime torrette binoculari del tempo alla portata degli astrofili.

Si trattava di una VIXEN con distanza interpupillare a scorrimento laterale dei barilotti (una torretta costosa per il tempo e anche molto rara: 25 anni fa quasi nessuno si sognava da noi di osservare con un visore bonoculare, cosa che invece oggi è stata scoperta da tutti).

“In unione con la torretta binoculare Vixen il VISAC tende a migliorare la visione di alcuni particolari contrastati sul pianeta e anche a limitare l’effetto sgradevole offerto dagli spikes. In compenso, il dettaglio sui particolari evanescenti o poco contrastati non migliora, anzi tende a impastarsi di più. Non amo molto questo genere di visori binoculari e trovo difficile ottenere un merging - per dirla come gli americani - perfetto delle immagini sui due occhi”.

Quella del Vixen VISAC fu una bella esperienza. Non lo amavo follemente, ma devo ammettere che mi piacque di più dei classici C8 vari anche accettate le sue maggiori limitazioni in campo planetario.

Il mio esemplare finì in una officina dove un allora giovane Franco Bellincioni mi mostrà la montatura equatoriale che stava costruendo, prototipo di quelle che poi sarebbero diventate le montature della sua produzione. Il VISAC gli serviva come strumento “test” per l’inseguimento e la valutazione dell’errore periodico.

Non so se lo abbia ancora...

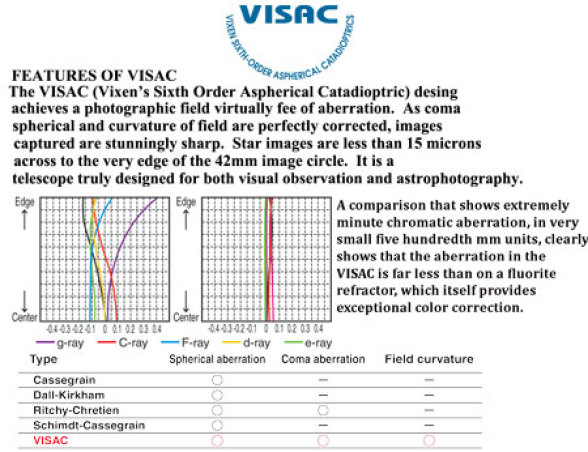

UN ARTICOLO INTERESSANTE di Chuck Hawks

Vixen (www.vixenoptics.com) is Japan's #1 telescope manufacturer and respected for their high quality products by astronomers around the world. Many Vixen telescopes incorporate unique design elements and their flagship VC200L is no exception. The VC200L (item #5870) is Vixen's premier, 8" (200mm) clear aperture, 1800mm focal length, catadioptric telescope (CAT). This f/9.0 modified Cassegrain represents the state of the art and it is among the most sophisticated 8" scopes, of any type, available today. It incorporates Vixen's Sixth Order Aspherical Catadioptric (VISAC) design and is intended to out perform standard Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes (SCT), an assertion we planned to check against our Celestron C8 control telescope in the course of this review. The corrector plate of conventional Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes corrects spherical aberration, but not coma or field curvature. The VC200L with VISAC corrects all three aberrations. It is, naturally, made by Vixen in Japan and comes with a five year warranty. The 2011 MSRP is $1899 for the VC200L optical tube assembly.

For astro imaging, the VC200L delivers astrograph quality. Here is what Vixen claims:

"The VISAC system provides high-definition star images to the edge of a wide viewing field and offers exceptionally outstanding performance in astrophotography. Even at the edge of the 35mm film format (larger CCD chips) stars are sharp (smaller than 15 micrometers). This is smaller than the resolution of fine quality CCD cameras, which means that the telescope does not limit the image quality. With its elaborate aspherical optical design, it achieves excellent image correction throughout the large illuminated field. (42mm diameter fully illuminated.)"

There are advantages and disadvantages to this design. On the plus side of the ledger are the superior optical correction, a Crayford focuser that eliminates all mirror shift, elimination of the dew problem endemic to Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov-Cassegrain front corrector lenses (the VC200L's main tube serves as a deep dew shield) and much shorter cool down times due to the open main tube. The obvious drawback is the open front of the optical tube that admits dust and debris, just like a Newtonian reflector. A less obvious disadvantage is the diffraction caused by the spider and a rather large secondary mirror obstruction that, inevitably, decreases contrast. (The VC-200L's secondary obstruction is 40% by diameter compared to 33.8% for a Celestron EdgeHD 8.)

The aspherical primary mirror in the VC200L is held in place by a retaining ring, rather than edge clips. This is claimed to decrease flare and increase contrast. Altogether, the VC200L is an extremely sophisticated, high quality telescope assembled with obvious care. Evidence of this is also found in the multiple collimation adjustments. You first adjust the secondary mirror tilt, then the primary mirror (if necessary). Even the drawtube/corrector lens system's alignment can be adjusted. (Our test scope's collimation was good out of the box and we kept our hands off the adjustments.) Due to its very rigid, cast aluminum, four-vane spider that is integral with the front cell, the VC200L holds its collimation better than most other open tube scopes, including all of the Newtonians we have used. Unlike a Newtonian, it should not have to be aligned frequently and certainly not for every session. However, its collimation is undoubtedly more fragile than an SCT or Mak and the VC200L deserves to be treated gently.

The VC200L that is the subject of this review was shipped with a carrying handle, full length Vixen dovetail mounting rail with steel mounting surface, 7x50mm straight-through finder scope, finder scope mount and 2" flip mirror star diagonal. Front and back caps for the telescope and finder scope were included, but not for the star diagonal.

The flip mirror diagonal is unusual. It is quite large, but allows straight through, as well as 90-degree, viewing (hence, the flip mirror feature). Eyepieces are retained by a thumbscrew sans compression ring. The back of the diagonal also accepts T-rings for mounting SLR cameras, eliminating the need for a T-mount adaptor. It is a handy diagonal for astrophotography, less so for visual use.

The 7x50mm finder scope focuses for distance (infinity) at the front and to your eye (for a sharp cross hair) at the integral eyepiece. It features an Illuminated cross-hair reticle, powered by a CR2032 lithium battery. The whole cross hair illuminates, not just a dot in the center. A rheostat to control brightness is located on the side of the finder's eyepiece tube. Made in China, it is a decent finder scope and the instruction sheet is printed in Japanese and English. The main body of the finder scope, as well as the mount, is white to match the VC200L optical tube

The supplied finder scope bracket is a good one. It uses three Allan head set screws (wrench provided) near the rear of the mounting tube to secure the scope and three thumbscrews at the front to align the finder with the main telescope. The thumbscrews have locking nuts to retain alignment once set. The mounting foot, naturally, fits the quick release Vixen shoe provided on the VC200L, as well as most other amateur telescopes.

Focusing the VC200L is by means of a smooth, 2" Crayford focuser attached to the back of the main tube, NOT by moving the primary mirror, as is the case with most Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes. A thumbscrew provides adjustable tension to prevent focuser creep when heavy eyepieces or cameras are used. It was immediately apparent that the VC200L's Crayford focuser is superior to any CAT we have previously used. It focuses like a high quality refractor, smooth and precise. 8" aperture, f/9-f/11 CAT's have a lot of inherent magnification, so a good focuser is very important, as well as a great convenience. Focusing has long been the Achilles' heel of CAT's that focus by moving the primary mirror (Celestron, Meade, Orion, Sky-Watcher, etc.). The latest VC200L's are advertised as coming with a two-speed focuser, but our sample was supplied with the optional single-speed focuser. It worked very well.

The VC200L is available as an OTA (optical tube only that includes the handle and Vixen mounting rail), with the accessories included with our test scope, or bundled with three different Vixen mounts. The latter include the GPD2, Sphinx SXW and Sphinx SXD. Since we already had a GPD2 mount on hand, we requested the basic OTA sans mount. Getting the accessory package (that we did not request) with the telescope was a pleasant surprise.

Along with the VC200L and its usual accessories, our friends at Vixen supplied one of their new #5449, 2" dielectric-coated star diagonals (2011 MSRP $179). This is a high quality star diagonal with a machined, internally baffled, two-piece body. The 1/10 wave mirror is made from quartz glass and boasts 99% reflectivity. It fully illuminates a 2" field of view without any vignetting and delivers true color images. A 1.25", compression ring, eyepiece adaptor is included. (Oculars in both the 2" and 1.25" openings are secured by compression rings to prevent scratching ocular mounting barrels.) End caps are included and it comes with a 5-year warranty. Since we preferred the #5449 star diagonal to the bulkier, flip mirror, two-way diagonal supplied with the VC200L, we used it for all of our critical viewing.

Observing

Needless to say, we had been anticipating the arrival of our VC200L. When it finally arrived at the beginning of June, after a long winter delay, we could hardly wait to get it outside under clear skies. Unfortunately, the weather during June and July in western Oregon is often unreliable and 2011 proved to be to be one of the worst years on record, with persistent overcast, clouds and occasional rain showers. Our opportunities to use the VC200L were frustratingly few and far between, trying our (already limited) patience.

We at Astronomy and Photography Online are primarily interested in visual astronomy and we tested the VX200L with our Mark 1 eyeballs. (After all, we reason, there are myriad outstanding astronomical images online and it is becoming increasingly pointless to replicate the effort already expended just to duplicate them.) We are willing to postulate that the VC200L's 42mm circle of full illumination, superior correction and flat field make it photographically superior to other CAT's. If astrophotography is your game you need read no farther, the VC200L is the 8" CAT to own.

To assist in our evaluation, we had a 4.5" Stellarvue SVT115T APO refractor and a Celestron C8 Starbright XLT to keep us honest, as well as a good selection of 1.25" and 2" oculars from Vixen, Celestron, Tele Vue, Meade and Burgess Optical in focal lengths from 40mm (45x) down to 4mm (450x). Here, listed by focal length, magnification and power-per-inch of clear aperture are some of the oculars we used in the VC200L at various times:

- 40mm = 45x, 5.6 ppi

- 32mm = 56x, 7.0 ppi

- 25mm = 72x, 9.0 ppi

- 18mm = 100x, 12.5 ppi

- 12mm = 150x, 18.8 ppi

- 8mm = 225x, 28.1 ppi

- 5mm = 360x, 45 ppi

- 8-24mm Zoom = 225-75x

The VC200L is really too big for comfortable terrestrial use, but our first chance to look through the big Vixen was during daylight. This gave us an opportunity to align the finder scope on a fir tree atop a distant hill, prior to taking it out at night for astronomical observing. Terrestrial observing let us check the VC200L's close-focusing distance, contrast, color saturation and overall terrestrial imaging ability using eyepieces of known quality. It also gave us a chance to use the Vixen flip mirror star diagonal in its straight-through viewing mode. (Convenient to look through, if you do not mind an upside-down, reversed view of the world!)

For convenience, we mounted the VC200L on a Stellarvue MG alt-azimuth mount and tripod. The MG is basically a medium size German Equatorial head turned 90-degrees. This rugged mount is intended for 4.5" f/7 (or smaller) refractors weighing up to about 15 pounds. The VC200L's weight is at this mount's upper limit and its magnification is probably beyond. However, the MG, although marginal, proved up to the task. For terrestrial use, an alt-azimuth mount is much nicer than an equatorial mount. (We later found the MG suitable for "quick look" astronomical use with the VC200L.)

Looking at the needles on the branch of a fir tree at a laser ranged 130 yards with a 32mm eyepiece, the central obstruction became visible as a round "shadow" in the center of the field of view. This focal length is too long for daylight observing. A 40mm Meade 5000 (2") ocular made the central shadow irritating, which is a shame, as the relatively low (45x) magnification would otherwise be quite useful in the daytime and the true field of view is great. Switching to a 25mm Celestron X-Cel (1.25") ocular (72x) improved matters and, although a faint shadow from the secondary could still be discerned, it was far less intrusive. We would say that 25mm is about the longest focal length ocular generally useful for terrestrial viewing.

Observing a branch in another fir tree lasered at 90 yards through the 25mm ocular, is was easy to see delicate gray moss growing at the base of the branch. Actually, quite interesting. Switching to an 18mm Tele Vue Radian eyepiece (100x) made the image larger and eliminated the remaining shadow of the secondary mirror housing, but the reduced contrast and color saturation, plus the magnified air movement, made viewing less pleasurable. (This on a mostly overcast day with a temperature of 73-degrees F.)

At 90 yards with an 18mm Radian, the focuser had exhausted its travel. There was only about 1mm of over-travel left. We would say that approximately 90 yards, depending on the ocular used, represents the VC200L's near focusing distance.

We made an unfair comparison to a Stellarvue SV115T 4.5" aperture refractor, focused on the same clump of moss. At the same 100x magnification (using an 8mm Radian in the refractor) it was clear that the refractor produced higher contrast and visual "snap," making it easier to see small details. Of course, the relatively short focal length (800mm) refractor, without a secondary obstruction, could be used at much lower magnification for highly detailed, wider field views.

All well and good, but it was time to get the Vixen out at night. The first chance to do so was on 16 June and Saturn was in a favorable position for viewing shortly after sunset. The evening weather was generally clear at our rural observing site, with a low temperature of about 50-degrees F after a daytime high in the low 70's. There was some light pollution from nearby residences, but less than would be found in a suburban setting.

Its rigid handle made attaching the VC200L to our M2 alt-azimuth mount easy. The chances of dropping the scope are much reduced with a handle that provides a secure grip. It is both a convenience and safety factor. The top surface of the handle also serves as a camera mount for piggyback photography and incorporates a ¼"x20 camera mounting screw for this purpose. The latter might also be used to mount a green laser pointer or red dot finder to assist in aiming the telescope. Either would be much easier to use than the straight-through optical finder we had to work with. (An upside down and backward finder drives us crazy.)

Saturn was available for viewing in the southwestern sky as soon as it got dark, so that is the object we observed. After using a 32mm eyepiece to get the telescope on target (our usual strategy for star hopping), we switched to an 8-24mm Click-Stop Zoom. We quickly discovered that the area between 18mm and 12mm gave the best results, so we switched to Tele Vue Radian oculars in those focal lengths. Both gave good views of the exotic planet, with the shadow of the ring system visible against the planet's surface. The 12mm, during brief moments of steady seeing, seemed to show a faint cloud band on the planet's surface. We would rate this view of Saturn under the prevailing conditions as good. Unfortunately, a thin cloud layer developed around midnight, putting an early end to observing.

In the course of viewing, we noticed that star images were, indeed, pinpoints from the center of the field of view to the edge. Vixen's claim that the VC200L offers a highly corrected, flat field of view is no idle boast. We also found that, with the telescope pointed up at a steep angle, it was necessary to use the focuser's tension screw to avoid creep with the heavy 2" star diagonal and an ocular on the back of the scope. Just a bit of tension did the trick and the focuser remained smooth, precise and a pleasure to use.

On the night of 20 June, the clouds dissipated and the sky cleared, leaving a night of good seeing (4 out of 5). This time we mounted the big Vixen on the GPD2 equatorial mount and, for comparison, a Stellarvue SV115T APO refractor on the MG mount. The two telescopes together made an impressive sight.

We were particularly interested in looking at M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, through the VC200L. The Whirlpool seems to hang below the handle of the Big Dipper (Ursa Major) and was well positioned in the sky. Under very dark sky conditions and with the right telescope, this flat-side-on spiral galaxy is one of the most impressive objects in the night sky. Unfortunately, although the seeing was good, the sky was not quite dark enough to make out the spiral galaxy's arms. We could see the companion galaxy through both telescopes, but no real detail in either. We used 40mm, 32mm, 25mm and 18mm oculars before deciding that 25mm gave the best view. Naturally, the shorter focal length eyepieces made the subject appear larger, but dimmer. The view through the 25mm seemed a reasonable compromise. Using our best "averted imagination," we could vaguely detect lighter and darker areas in the Whirlpool.

The Stellarvue SV115T did not do as well on M51. Given its substantially lower magnification with any given eyepiece, the image was smaller, but no more detailed. We were seeing the usual fuzzy spot marked by increased brightness at the center of the galaxy.

M13, the great globular cluster in Hercules, was an impressive sight through both telescopes. Both gave very sharp views of the stars, but the VC200L resolved deeper into the core of the cluster. It produced a noticeably brighter view at similar magnification. The flat viewing field of the VC200L was appreciated and made accurate focusing on off center stars possible. We are disappointed to report that the ambient light pollution, although not great, impeded resolving M13 to its core. We had hoped that the ultra-sharp VC200L might be able to achieve this.

We quickly tired of trying to peer through the VC200L's straight through finder with the telescope pointed high in the sky. Back and neck strain made this very uncomfortable. Indeed, we found it easier to aim the Stellarvue at an object, turn on its green laser pointer and aim the VC200L where the laser was pointing. A 40mm eyepiece in the VC200L had sufficient field of view to allow us to find the laser beam and follow it to the target.

Alberio, the gold and blue star pair at the foot of the Northern Cross (Cygnus) was inspected last. This 3.1-5.1 magnitude double is 35 arc-seconds apart and easily split. Through the VC200L, the different colors of the two stars were evident. Brightness not being much of an issue, we tried a variety of oculars of increasing magnification, with the shortest being 8mm. Alberio is one of the most beautiful double stars in the heavens and the VC200L handled it nicely.

It was now 2:00 AM and everything was sopping wet from the heavy dew, including our StarBound observing chair, so we decided to pack it in. Unaffected by the dampness, however, was the primary mirror of the VC200L. Its deep tube design (and judicious use of the front lens cap) demonstrated its worth on this night. Given our long experience with the type, we can say with certainty that the corrector of an 8" SCT would have been thoroughly covered with dew.

We had hoped to get the VC200L out at least once more before publishing this review and the weather/seeing conditions finally relented on the night of 8 July. The moon was it its quarter phase, which flooded our remote site with unwanted reflected light, it was windy and there was substantial air boiling after a 77-degree F day. The overnight low was about 50-degrees. The observing conditions went from below average to something approaching average as the night progressed and were the primary factor limiting what we could see, but at least we were finally able to get the Vixen VC200L and a Celestron C8 Starbright XLT in the field together at a remote site in the hills.

Chuck Hawks, Jim Fleck and Bob Fleck were in attendance and a surprise addition was Editor Gordon Landers, just returned from a star party in Likely, CA with his new Stellarvue SV160, a 6.3" APO triplet (oil spaced) refractor with a 1300mm focal length that retails for $8990 online. We were able to compare the three telescopes at approximately the same magnification while viewing the moon, M51 (Whirlpool galaxy), splitting the "Double Double" in Lyra and M57 (Ring nebula). Finally, we aimed the two CAT's at a star field in the Milky Way.

Note at the outset that these are three superior telescopes. The Celestron C8 XLT is the least expensive and it is a better scope than most people will ever own. (A review of this particular C8 can be found on the Astronomy and Photography Online index page.) We were comparing the expert class Vixen to an advanced class Schmidt-Cassegrain and an expert class, one of a kind refractor. We were in telescope Nirvana!

Moon: Earth's binary planet/satellite is the most highly detailed object we can view in the heavens and the only planetary object we observed. We all agreed the Stellarvue refractor demonstrated its superior contrast by providing the best views. However, both the VC200L and C8 revealed plenty of lunar detail, limited more by the local atmospheric conditions than the telescopes themselves. Chuck and Jim thought that the Vixen edged out the Celestron for lunar viewing, while Bob had the opposite impression of the two CAT's.

M51 Whirlpool Galaxy: All three telescopes showed the Whirlpool and its smaller companion as fuzzy areas with a bright center. None of them showed clear dust lanes or spiral arms. Bob thought the SV160 provided the best view, followed by the C8 and the VC200L. Jim rated the C8 first, VC200L second and SV160 third. Chuck concluded that the VC200L and C8 were equal and liked the view through both slightly better than the view through the SV 160. Gordon thought that all three scopes were too close to call.

"Double Double" in Lyra: Splitting the binary star pairs showed the SV160 to its best advantage. All three scopes could easily resolve all four stars with a variety of oculars, but the separation was clearest when viewed through the Stellarvue. Comparing the two CAT's, Chuck and Gordon slightly preferred the VC200L, Bob slightly preferred the C8 and Jim rated it a tie.

M57 Ring Nebula: To no one's surprise, the famous Ring in Lyra showed clearly in both CAT's. Gordon had the Stellarvue on globular clusters M4 and M80 while Chuck, Jim and Bob compared the CAT's on M57. All three rated the two 8" scopes essentially equal when viewing the ring.

Star Field: At one point in the session, Chuck pointed the VC200L at a random star field in the Milky Way, using the 40mm Meade 5000 2" eyepiece. The relatively dense spread of pinpoint star images from edge to edge of the wide field of view was one of the most spectacular views of the evening. Jim pointed the C8 at the same general area of the Milky Way, but the C8 could not match the Vixen's superior correction. The VC200L's sharpness and flat field were displayed to good advantage by this test, which was the VC200L's most dominant moment. It would clearly be a superior CAT for viewing open clusters and similar applications where edge to edge sharpness is at a premium.

The VC200L's 2" focuser is more convenient to use with a 2" star diagonal than the C8 (and most other SCT's). You just slide in any standard 2" diagonal. This makes switching from 1.25" to 2" oculars a snap. With a C8, you have to unscrew the 1.25" visual back and screw-on the proprietary Celestron 2" star diagonal.

The Vixen's other undeniable attribute is its Crayford focuser, which we found clearly superior to the moving primary mirror focusing system used in the C8 and other SCT's. All four observers agreed that they found the Vixen's focuser easier to use and more precise.

Keep in mind that viewing through any astronomical telescope is a subjective experience. It depends as much or more on the existing conditions, eyesight and experience of the observer as it does the telescope. As they say in advertising, but seldom mention in telescope reviews, your results may vary.

Conclusion

As you might expect from its generous clear aperture and rather large secondary obstruction, the Vixen VC200L is primarily a deep sky telescope. It has the focal length and consequent magnification to provide good views of the moon and planets, but cannot equal the contrast of an APO refractor. It is when observing deep sky objects that it is superior. We would rate it a good all-around astronomical telescope and excellent for deep sky use. As of this writing, the VC200L scores second only to the (five times more expensive!) SV160 at the top of our "Astronomical Telescope Comparison" article. (Available on the Astronomy and Photography Online index page.)

As Astronomy and Photography Online's Jim Fleck likes to point out, for most amateur astronomers with 8" and smaller scopes, planetary observing is limited primarily to the moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Venus' phases can be observed, but no surface details can be seen through its 100% cloud cover. Everything else is a deep sky object and there are thousands of them to observe. Thus, according to Jim, deep sky capability should take precedence over planetary capability in a general purpose amateur telescope.

If this analysis makes sense to you and you are ready for an 8" instrument, give the Vixen VC200L serious consideration. Its initial purchase price is higher than most 8" CAT's, but its pinpoint star images and flat-field view are impressive and its focuser is superior. Given its excellent quality and performance, it should be a lifetime investment.

VC-200 (VISAC) o VMC-200? - perché non sono la stessa cosa...

Il Vixen VC-200 (VISAC) sopra e il Vixen VCM-200 sotto.

VISAC 200L

VISAC Aspherical Mirror Reflector

The VC 200L Reflector is an 8" f/9.0 highly corrected, highly specialized telescope for astro imaging. Vixen's unique catadioptric design features a high precision sixth order aspherical primary mirror, a convex secondary mirror and triplet corrector lens. VISAC is an abbreviation for Vixen's Six-Order Aspherical Cassegrain. The primary mirror is held by a retaining ring, instead of hooks, to decrease flare and enhance contrast.

The VISAC System provides high-definition star images to the edge of a wide viewing field and offers exceptionally outstanding performance in astrophotography. Even at the edge of the 35mm film format (larger CCD chips) stars are sharp (smaller than 15 micrometers). This is smaller than the resolution of fine quality CCD cameras, which means that the telescope does not limit the image quality. With its elaborate aspherical optical design, it achieves excellent image correction throughout the large illuminated field. (42mm diameter fully illuminated) Astronomy Technology Review states: "The VC200L focuser is one of the smoothest I've ever tested...overall the visual image quality of the VC200L was quite impressive...and is a step up from the typical Schmidt-Cassegrain" Read the full review in Astronomy Technology Today. With the f/6.4 reducer you get much shorter exposure times. Vixen's Dual Speed Focuser and compression ring are included. Check out Drew Sullivan's Review

VMC200L

The VMC200L Reflector Telescope is a unique 200mm, 8" catadioptric optical system. It incorporates a primary mirror and a meniscus corrector just before a secondary mirror. By doing so, light is corrected twice on the optical path. The end result is that spherical aberration and field curvature are corrected to a high degree of optical performance. The VMC200L’s primary mirror is f/2.5; the compound optical system is f/9.75. This makes the system much more compact and portable than its competition. With the optical correction placed before the secondary mirror, the VMC200L avoids the necessity of having a corrector plate and all the dewing problems associated with a closed optical tube.

An additional key feature is the rack and pinion focusing that is placed behind the primary mirror. The use of this focusing system eliminates the image shift associated with most other SCT systems. This is especially important when using high power magnification or astro-photography. When focusing, the image is stable and easy to adjust. Astronomy Technology says "the f/9.75 focal ratio is noticeably faster than the typical Maksutov design ..which translates into a wider true field of view. Reaching focus is easy...Lightweight, portable, 8 inches of aperture, fast cool down, zero image shift, and reasonably priced - I guess it may be possible to have your cake and eat it too." Read the full review in Astronomy Technology Today. The VMC200L Reflector is made in Japan and is covered by a Five Year Warranty.

The VMC200L Refelctor features a catadioptric "Field Maksutov" type design with two spherical mirrors and a meniscus corrector element behind the secondary mirror passed twice by the light. The open tube has shorter cool down times compared to 8" SCTs

200mm (8”) ; precision spherical mirror

CONSIDERAZIONI STATICHE

Benché sia chiaro che lo strumento mi piace (in caso contrario non lo avrei ricomprato), mi permetto alcune considerazioni di carattere pratico/estetico.

La cinghia di impugnatura è molto particolare, vintage, un poco demodé, ha il suo fascino ma obiettivamente una maniglia (come nella versione ristilizzata) sarebbe più comoda da usare.

Splendida la livrea generale con una forma più allungata rispetto a quella da “fustino del Dixan” dei compound SC e decisamente più bella la culatta verde rispetto a quella orribilmente colorata di bianco latte attuale.

Ben fatta la barra a passo Vixen che corre lungo tutto il tubo ma perdonatemi, le barre di questa sezione non le gradisco molto preferndo loro il passo "Losmandy".

Grazie al cielo non servono anelli porta ottica in compenso e mi chiedo se i possessori di fustini da detersivo chiamati telescopi e sostenuti con osceni anelli si siano mai soffermati in modo critico a valutare l’armonia dell’insieme.

Che un telescopio abbia come scopo principale quello di mostrare le stelle nel migliore dei modi non discuto ma le soluzioni ad anelli su tubi corti, pur molto solide, appaiono tanto brutte da diventare offensive.

Per il resto solo complimenti: opacizzazione interna del tubo di buon livello, costruzione meccanica di pregio, qualità ottica in abbondanza, regolabilità degli elementi principali ai massimi livelli.

Per semplice curiosità riporto a seguire alcune immagini di come appariva lo strumento sul sito del venditore prima del mio acquisto (e solo per il colore del supporto del cercatore ero tentato di non comprare nulla…).

STAR TEST, COLLIMAZIONE E CONSIDERAZIONI GENERALI

Il caldo afoso della Milano di agosto 2017, con temperature record, non aiuta a gestire calma e precisione ma avevo bisogno di testare lo strumento prima di portarlo in alta montagna e così ho accettato una sera di zanzare e sudore.

Il primo check con un cheshire di marca Intes sembrava offrire responso accettabilmente positivo ma una volta posto lo strumento sotto il cielo ancora chiaro e inquadrato Arcturus (Alpha Bootis) mi sono accorto di essere ben lontano da una posizione corretta dei due specchi.

Agendo sulle viti a brugola del primario e secondario ho avuto la sensazione che il precedente proprietario non si fosse mai nemmeno preoccupato della collimazione dello strumento come del resto non sembrava aver posto attenzione ai basculamenti del focheggiatore che ho dovuto sistemare prima di mettere in postazione il telescopio.

Le operazioni di collimazione mi hanno impegnato per quasi un’ora e ho dovuto ritoccarle man mano che lo strumento si assestava e mentre operavo anche saggi sulla assialità del gruppo di focheggiatura.

Quando il cielo si era oramai completamente scurito (nei limiti di una grande città come Milano) ho potuto valutare un poco le ottiche che, nonostante un seeing non amico, hanno dimostrato di essere ben corrette e lavorate. Solo in prossimità dello zenit e zone limitrofe ho potuto focalizzare correttamente a ingrandimenti superiori ai 300x (360x con oculare LE 5mm.) riscontrando una buona resa generale con quattro spikes molto pronunciati ma ben bilanciati nella distribuzione luminosa e privi di difetti come baffi aggiuntivi. Ben concentriche le immagini sia in intra che in extra focale e molto preciso il punto di fuoco, cosa piacevole soprattutto per un cassegrain molto ostruito testimoniando una correzione delle ottiche sopra la media.

L’inversione del meridiano e qualche spostamento di oltre 90° non hanno messo in difficoltà la collimazione che è stata mantenuta in modo quasi perfetto, merito della meccanica ben dimensionata. Molto positiva anche la apparente assenza di residui cromatici introdotti dal correttore inserito poco prima del focheggiatore e internamente al canotto paraluce dello specchio primario.

A questo proposito vorrei spendere alcune considerazioni sulle scelte operate, a livello progettuale e meccanico, dai tecnici Vixen. Benché si legga di perplessità relative al sostegno dello specchio secondario con razze molto spesse (circa 5 mm.) e di astrofili che le hanno fatte ridurre a circa 1/4 per ottenere maggior contrasto nelle immagini finali mi sento di non condividere né le critiche né gli interventi “after market” suggeriti.

Il VISAC nasce non come alternativa ai catadiottrici classici Meade e Celestron ma come strumento a sé stante con finalità ben definite e che sono state in larga parte non comprese dal mercato degli anni ’90. La generosa ostruzione e tutta la struttura meccanica che contraddistingue il telescopio parlano chiaro. Il cassegrain giapponese, con una focale nativa “corta” (è un f.9 con possibilità di essere ridotto a f 6.4 circa con l’apposito correttore), doveva fornire all’utente una macchina ben studiata per l’indagine fotografica a media focale degli oggetti del cielo profondo. In quest’ottica le soluzioni adottate rispondono in modo perfetto. Il secondario è grande e intercetta tutto il fascio ottico permettendo un campo di piena luce generoso. Le sue dimensioni e il peso relativo (un po’ come accade con gli RC a cui gli astrofili moderni si sono abituati) richiedono supporti in grado non solo di mantenere lo specchio nella posizione voluta ma anche e soprattutto di permetterne le adeguate regolazioni senza il rischio di introdurre deformazioni alla meccanica. Lo stesso tubo in alluminio, dello spessore di 2 mm. circa, dotato di una barra a passo Vixen incernierata lungo tutta la lunghezza, assolve bene all’esigenza di una rigidità costante e inalterabile, anche in virtù delle sue dimensioni generali.

La culatta posteriore è ben spessa, correttamente sagomata, strutturalmente portante e funziona in modo egregio permettendo non solo una precisa collimazione del primario (con tre coppie di viti poste quasi a ridosso della circonferenza) ma anche un supporto indeformabile a tutto il gruppo di focheggiatura e alle sue regolazioni.

Tentare di “trasformare” il VISAC in uno strumento diverso significa squalificarne l’essenza e non comprenderne la logica prima.

Anche il focheggiatore merita plausi generali. Benché non sia morbidissimo non presenta alcun tipo di cedimento né di impuntamento lungo tutta la sua corsa che appare piuttosto fluida e costante. Non possiede abbia l’aplomb di un Feather Touch ma lavora in modo egregio e sicuramente permette un adeguato supporto alle macchine fotografiche sia ad emulsione del tempo che alle DSLR odierne senza patemi di slittamento alcuno.

Mentre lavoravo con il VISAC, operando sia sulla collimazione sia riprendendo confidenza dopo due decadi di oblio, non ho potuto non pensare in modo comparativo al mio Takahashi CN-212.

Gli strumenti appaiono diversi ma la loro configurazione primaria è comparabile anche se diametri e focali differiscono (200/1800 il VISAC e 212/2640 il CN).

Per quanto il cugino Takahashi sia strumento superbo non posso che preferire il focheggiatore Vixen che non trasla il primario e che quindi non impone alcun fenomeno di focus shift. Anche le dimensioni e il peso giocano a favore del VISAC che accusa quasi quattro chili in meno alla prova “costume” sulla bilancia permettendo l’impiego di montature molto più piccole (impensabile installare un CN-212 su una Great Polaris ad esempio…)

Dall’altro canto risulta impossibile per il VC eguagliare la pulizia e contrasto di immagine del CN-212 che è e resta uno dei migliori cassegrain di media taglia che abbia mai avuto occasione di usare (non per nulla è uno dei miei telescopi preferiti).

Sarebbe però riduttivo e sbagliato paragonarli (anche se molti lo fanno) perché le caratteristiche del VISAC (come quelle di doppio telescopio newton e cassegrain del Takahashi) sono uniche o quasi.

Sopra: breve GIF creata con tre immagini riprese il 18/6/2018 da Milano, seeing 6/10,

VISAC 200L e barlow 2x Celestron Ultima su camera IMX 224 a colori.

SOTTO UN CIELO TERSO E SCURO

La prima sera si annunciava con un cielo di montagna indeciso tra l’azzurro intenso e grandi nubi orografiche bianche e grigie ma è andata migliorando progressivamente sino al sorgere della Luna nel primo imbrunire e poi proseguire con un terso cielo freddo, nonostante l’inizio di agosto, ma bianco per via della grande luce riflessa dal nostro satellite.

Pur sapendo di non potermi spingere in profondità a causa del chiarore di fondo mi sono dedicato sia all’osservazione di alcuni principali oggetti del cielo profondo sia alla valutazione della focalizzazione dello strumento.

Nel pomeriggio, scontento per gli scossoni del viaggio in trattore che avevano dovuto subire sia il VISAC che il Comet Catcher (oggetto di altro test su questo sito), ho smontato completamente il cassegrain giapponese e riallineato i due specchi e il focheggiatore.

Alla prova sul cielo l’opera di collimazione si è fatta valere e un solo finale ritocco è servito a portare la condizione operativa dello strumento prossima alla perfezione.

I risultati sono stati esaltanti per la finezza che i soggetti stellari hanno offerto con una pulizia e qualità sconosciuti anche ai migliori Schmidt Cassegrain a campo corretto che ho potuto provare (Meade e Celestron in primis). Le immagini non avrebbero sfigurato nemmeno paragonate a quelle di un buon rifrattore da 15 cm. ma con maggiore luminosità e una propensione all’indagine degli oggetti deboli più spiccata.

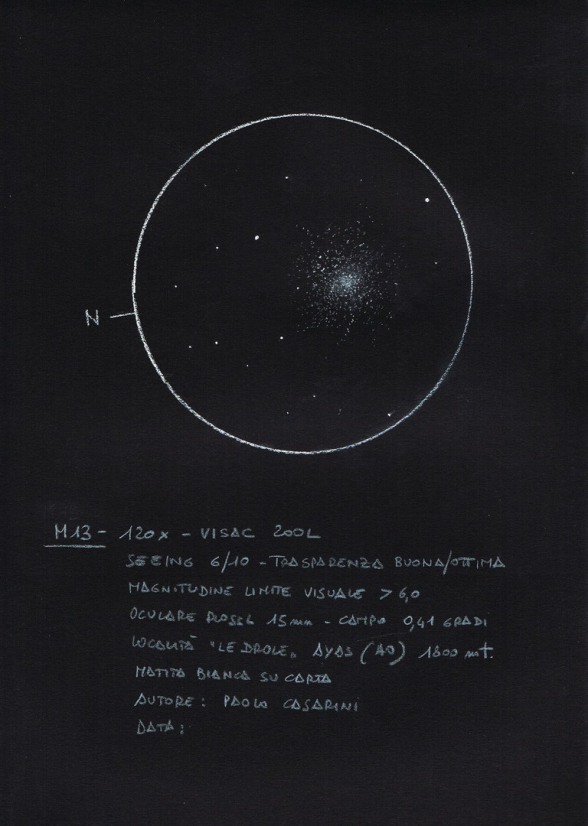

Le condizioni del cielo limitavano il contrasto e la magnitudine limite in modo drastico ma gli oggetti scelti a campione hanno comunque saputo offrire indicazioni precise sulla qualità dello strumento. I due principali ammassi globulari in Ercole, M13 e M92, mi hanno permesso di spingere senza alcun problema gli ingrandimenti a 260x con l’oculare zoom mantenendo le stelle finissime capocchie di spillo e consentendo risoluzione fin nelle zone centrali degli ammassi.

Ho indugiato lungamente nella loro osservazione e non ho alcuna difficoltà ad ammettere che, luminosità e risoluzione a parte (che dipendono dal diametro), ben pochi altri strumenti mi hanno concesso a memoria tanta qualità di immagine su questi due globulari (e tra questi nessun Schmidt Cassegrain).

Anche il “wild duck cluster”, ammasso M11, si è rivelato in tutta la sua bellezza con stelle finissime e la principale gialla ben luminosa nonostante il bianco lattiginoso del cielo. Assaporando quanto avrei potuto osservare al novilunio ho dedicato tempo ad alcuni sistemi binari ultimando la serata con la Polare e compagna che mi hanno regalato una delle più belle osservazioni che sappia ricordare. Credo di non essere lontano dal vero dicendo che la combinazione di saturazione, campo corretto, pulizia di immagine e luminosità ne facciano una delle più piacevoli personali osservazioni di questo sistema doppio se si esclude quella con il rifrattore TMB 203 f9 che possedevo anni fa o con l’attuale FCT-150.

Superata la mezzanotte e con la piacevole sensazione di freddo (a cui non ero più abituato dopo il caldo torrido di Milano in questa estate del 2017) ho smontato lo strumento e portato la montatura ATLUX nel piccolo ma attrezzato “laboratorio” montano per tentare di risolvere un problema di “singhiozzo” nel l’asse del motore di ascensione retta.

La sera del 9 agosto ho rimontato sulla ATLUX, a cui sono finalmente riuscito a correggere il problema in AR, il nostro VISAC sfidando un cielo che si annunciava tempestoso per l’imminente arrivo di una perturbazione.

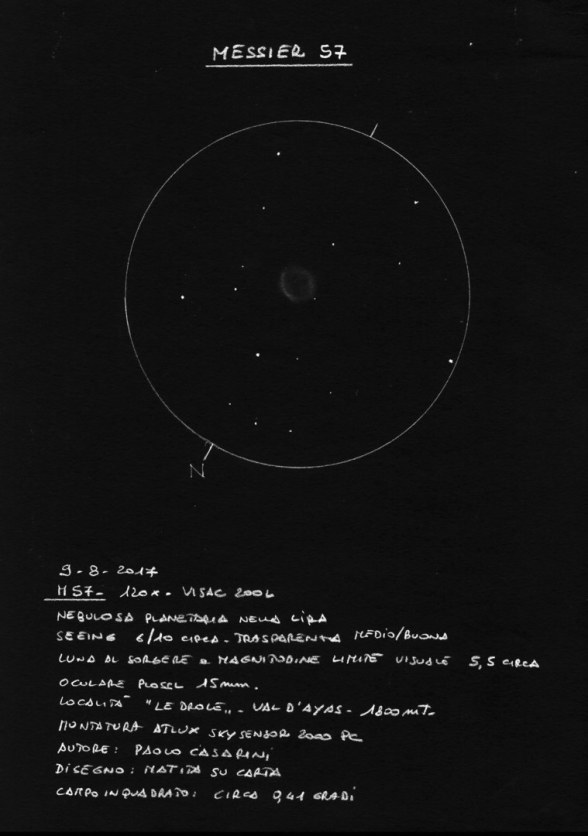

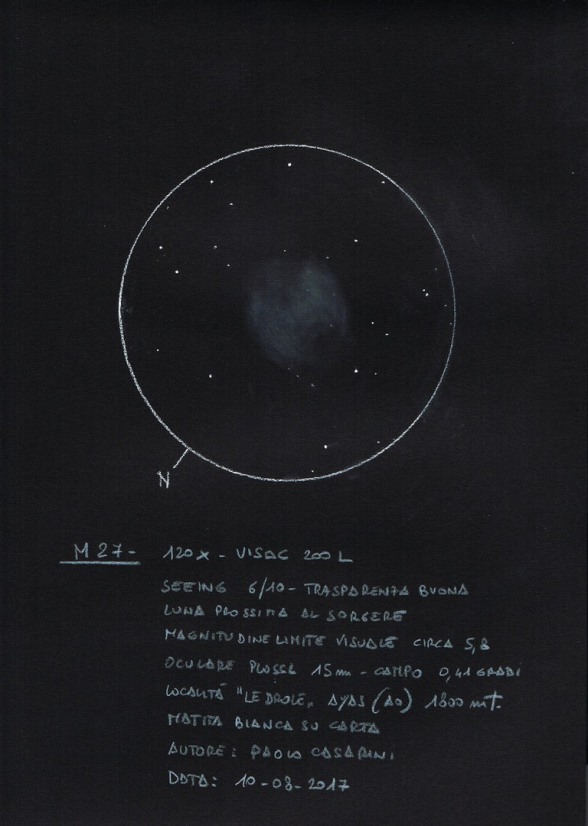

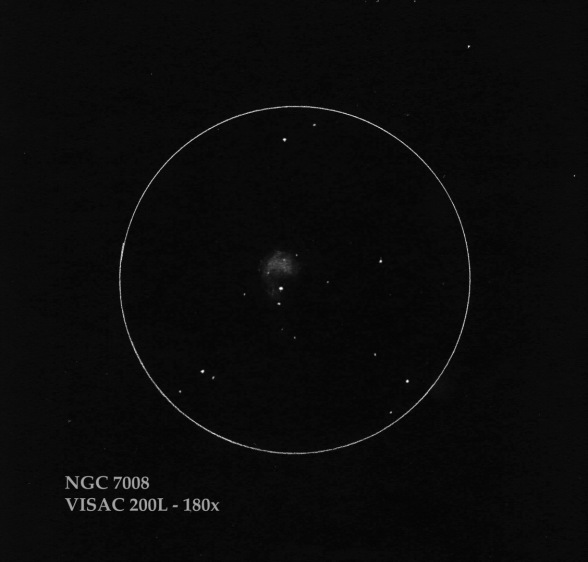

La volontà era quella di dedicarmi ad un disegno e viste le condizioni di luminosità del cielo che non mi permettevano di andare oltre la magnitudine 4,5 o poco più a occhio nudo ho puntato la facile M57 e cominciato a segnare le principali stelle che comparivano nel campo dell’oculare plossl da 15mm (120x e campo reale di circa 0,4°).

La luce diffusa non mi ha permesso di cogliere le stelle più deboli e il disegno risulta così “povero” di stelle di campo. Ho faticato un po’ a registrare gli astri più deboli disponibili in compenso la loro posizione e luminosità reciproca è stata riportata con buona precisione così come i pochi dettagli visibili sulla nebulosa.

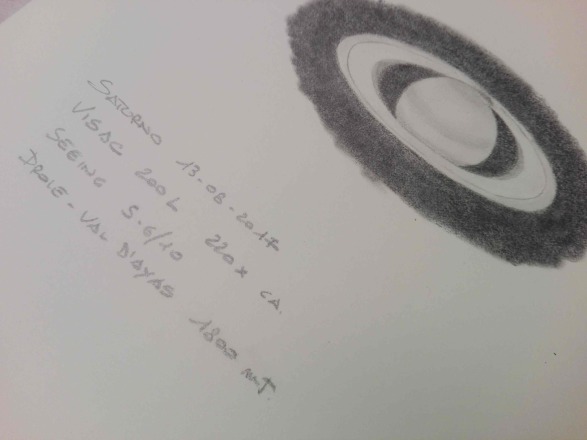

Quando le nubi grigio biancastro hanno coperto la costellazione della Lira ho potuto rivolgermi solamente ad ovest dove, basso, Saturno si avviava al crinale della vicina montagna.

Il seeing limitato e la scarsa trasparenza non suggerivano grandi speranze ma il pianeta mi ha comunque regalato una bella immagine anche se fortemente influenzata dalle condizioni di turbolenza.

Con l’oculare Orbinar zoom (7,2-21,5mm. si veda articolo su questo sito) ho trovato il migliore ingrandimento tra nitidezza e dettaglio in circa 200x riuscendo a godere di una serie insperata di particolari. La divisione di Cassini era leggibile per quasi tutta la lunghezza degli anelli andando a confondersi solamente nella parte antistante al globo che in compenso mostrava ben due bande con quella più equatoriale più scura e quella tropicale più debole e accennata. Una ben visibile variazione di tinta al polo si mostrava come regione scura e l’ombra del pianeta sugli anelli si coglieva bene anche se per una porzione molto limitata data la prospettiva della posizione solare. Ovviamente le condizioni di densità dell’aria non mi hanno permesso di cogliere il tenue anello “C” ma la prestazione del VISAC ha comunque lasciato ben intendere le sue potenzialità e se solo il pianeta fosse stato più alto e la serata migliore avrei sicuramente goduto di un grande spettacolo.

L’occasione si è ripetuta qualche sera dopo in condizioni sia di trasparenza che di seeing migliori, benché la turbolenza in montagna sia sempre più accentuata che in pianura. L’aria tremolava e un po’ di vento rendeva instabile la visione ma a poco più di 200x Saturno offriva una serie di particolari estremamente incisi. La Cassini era visibile come una nettissima strisciolina scura molto contrastata, l’anello C finalmente si staccava dalla parte di cielo dentro alle anse e la pulizia del pianeta e degli anelli era superiore a quella offerta in precedenza.

Nei brevi momenti in cui il seeing permetteva ai particolari di andare perfettamente a fuoco l’immagine è apparsa molto buona.

Se si fa eccezione per il binoscopio da 130/1000 a rifrazione con cui osservo normalmente il cielo profondo e il più piccolo binocolo 20/100 angolato dedicato alle sole nebulose oscure, ho eletto ultimamente il VISAC 200 come mio principale telescopio dedicato agli oggetti “deboli” della volta stellata.

Avendo avuto strumenti ben più grandi (fino ai 50 centimetri) precedentemente impiegati a questo scopo si potrebbe dire che la scelta rappresenti un notevole passo indietro.

Se però tralasciamo i grossi dobson che per ovvi motivi non dispongono né di un puntamento automatico né di un inseguimento siderale (se non in rarissimi casi) devo dire di non sentire grande nostalgia per sistemi compound più grandi.

Il guadagno luminoso che un 8 pollici ben corretto offre sotto un cielo molto favorevole (e quindi con una magnitudine visuale allo zenit pari o superiore alla sesta e una turbolenza non eccessiva) risulta più che sufficiente per la stragrande maggior parte degli oggetti amatoriali.

La prima impressione, venendo da aperture molto maggiori, è quella di “vedere poco” ma la quiete e l’attenzione, la scelta degli oculari giusti e un approccio più tranquillo alla osservazione portano in poco tempo a valorizzare maggiormente alcuni aspetti della visione in sé come ad esempio la puntiformità e finezza stellare oltre alla correzione del campo inquadrato.

Queste non sono un sostituto alla raccolta di luce perché un 30 cm. permetterà sempre e comunque una maggiore luminosità dei campi stellari, degli ammassi globulari e anche di qualche nebulosa e galassia. La differenza che però sembra in prima istanza importante tende a stemperarsi molto e a ridursi a pochi dati in più, almeno su gran parte dei soggetti Messier e NGC (quantomeno di quelli alla portata di telescopi amatoriali).

Questo, e comprenderlo in modo profondo mi ha richiesto molti anni, mi ha fatto accettare con maggiore benevolenza un diametro più modesto e porre più attenzione al dato geometrico dell’immagine restituita.

Probabilmente un VISAC da 25 cm. potrebbe rappresentare per il mio tipo di osservazione il compromesso in assoluto migliore ma purtroppo la casa giapponese non lo produce. Il VMC 260 (ottica a dir poco eccezionale!) non ne rappresenta una alternativa vera avendo un rapporto focale e un prezzo che lo proiettano in un mondo "diverso" sia per tipologia di impiego che per fascia di mercato (si consideri che costa quasi il doppio rispetto ad un classico C11 ma vale ance decisamente di più essendo a quest'ultimo "fustino" decisamente superiore sotto ogni aspetto).

A queste considerazioni se ne aggiunge una molto importante e che riguarda il campo di impiego ristretto a cui si vuole dedicare il proprio tempo e strumento.

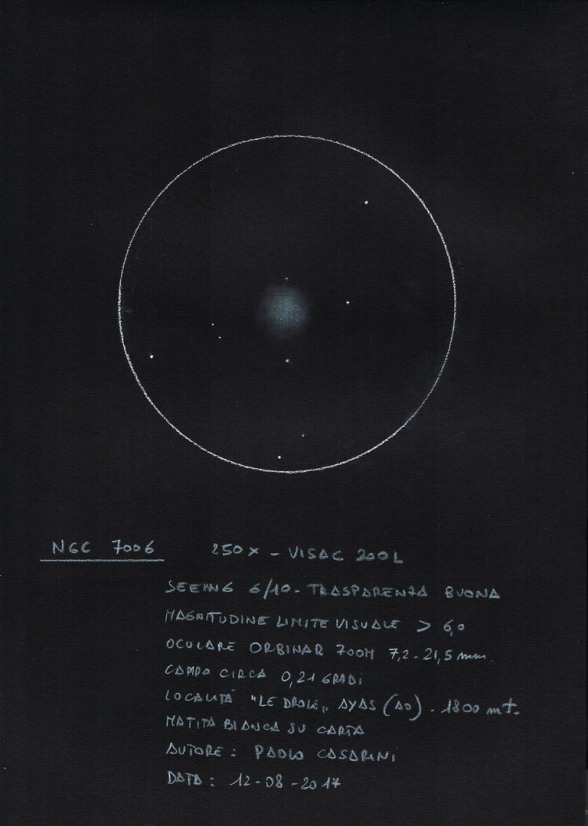

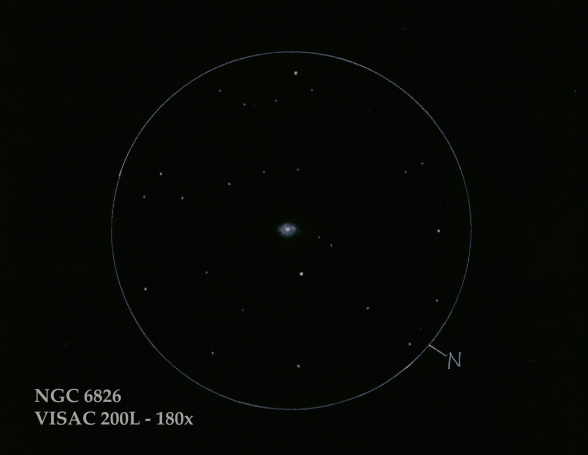

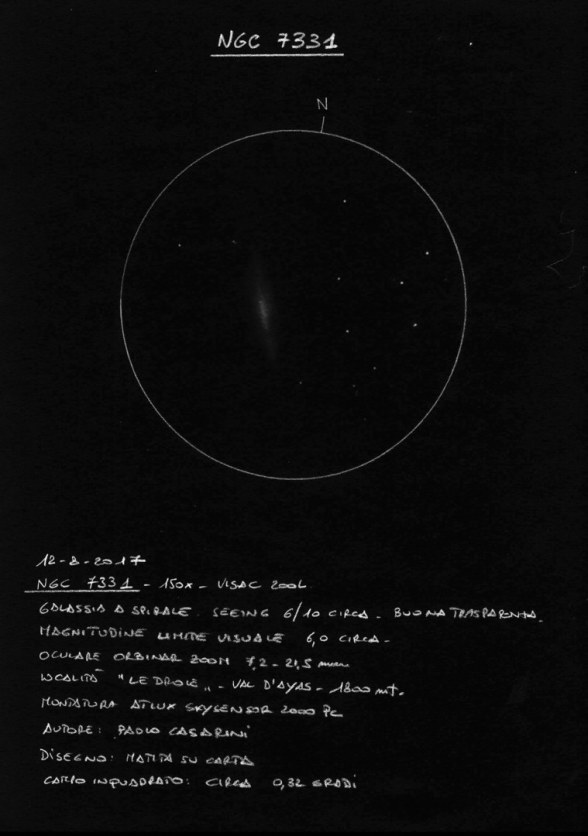

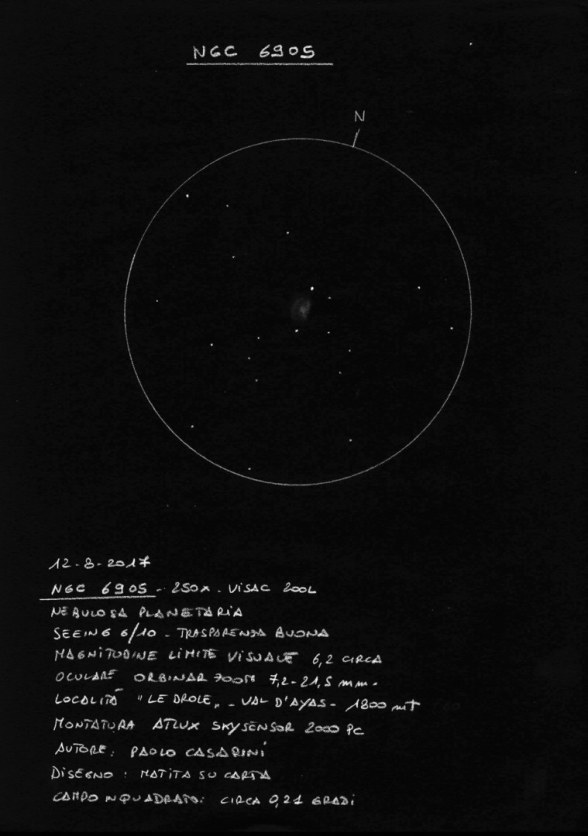

La rediviva propensione al disegno ha trovato molta complicità nel cassegrain Vixen. Il campo corretto e la focale nativa, unita ad un classico plossl da 15 mm. (nel mio caso un Meade serie 4000) offre una amalgama perfetta per il disegno astronomico che so sviluppare. Lavorare con 120 ingrandimenti e un campo di 0,4° permette di restringere in modo significativo ma non eccessivo il campo inquadrato, ridurre il numero di stelle di fondo da riportare (pur mantenendo una valida contestualizzazione agli oggetti tipici) e avere un rapporto di contrasto ottimale.

Disegni a matita bianca su cartoncino raffiguranti l'immagine telescopica ottenuta con il VISAC 200L dei soggetti rappresentati.

ALTA RISOLUZIONE: STELLE DOPPIE

Il motto secondo cui il VISAC 200L non sarebbe adatto all’alta risoluzione è pari a quello che vede incapaci i suoi possessori (o la maggioranza di essi così come coloro che "parlano a vanvera") a collimarlo in modo proprio e corretto.

Durante il periodo di test infatti, opportunamente collimato e gestito, il Casegrain derivato Vixen ha sfoggiato immagini dei sistemi multipli ben superiori a quelle alla portata dei comuni Schmdit Cassegrain commerciali di nome Meade o Celestron con immagini decisamente più pulite e capaci di sostener un numero di ingrandimenti maggiori.

Benché esistano, nel limite dei 20 cm., strumenti anche più prestazioni (tra i quali porrei il OMC-200 F20 Orion, e anche i Mewlon 180 e 210 Takahashi, così come i rifrattori apocromatici da 15 cm. e il mio MT-160 a f8.3), il buon Visac 200L ha dimostrato di saper fare “molto bene” non facendo rimpiangere nemmeno in questo difficile campo di applicazione strumenti sulla carta più specializzati.

CONCLUSIONI

Il VISAC è stato, a torto, mal compreso dagli astrofili nostrani.

Se la colpa sia da attribuire ad una errata pubblicità Vixen (onestamente mai tanto azzeccata per nessun articolo e generalmente "opaca") o alla scarsa preparazione degli utenti italiani (realtà in molti casi incontrovertibile) poco importa. La verità è che il cassegrain giapponese era uno strumento superbo venticinque anni fa esattamente come lo è ancora oggi, sotto quasi tutti i punti di vista.

E’ capace di offrire un ampio campo corretto utile sia in visuale che in fotografia, può diventare un astrografo abbastanza rapido (f 6.4) con il suo riduttore dedicato (ultimamente rivisto e migliorato nella versione HD con una correzione ancora più spinta delle prestazioni fuori asse e proposto al sostenibile prezzo di 245,00 euro), e sa anche essere un buon performer planetario.

Le critiche che gli sono state mosse sono incomprensibili e dettate più dalla voglia che fosse qualcosa d’altro più che dalla attenta disanima delle caratteristiche progettuali e della loro rispondenza pratica all’uso.

E’ superiore agli Schmidt Cassegrain classici e anche ai più recenti HD-ACF con l’innegabile vantaggio di una meccanica più robusta e una più facile gestione termica delle sue componenti e rende decisamente di più nell'osservazione visuale sia del cielo profondo che dei sistemi multipli a medio e alto ingrandimento.

Infine è leggero (6 chilogrammi per il OTA completo di barra solidale, cercatore e supporto per ottica secondaria) e con una distribuzione dei pesi molto favorevole e prossima a 1/4-3/4 (la culatta la parte più pesante) benché richieda una montatura solida per essere portato alle sue prestazioni massime.

Lo ripeterò allo sfinimento: un cassegrain da 20 cm. ha bisogno come minimo di una montatura EQ6 o superiore, di una SP DX, di una Ioptron serie 45, di una Vixen SXD-2, di una Celestron con portata nominale da circa 20kg (e questo anche se l’ottica pesa “solamente” 6 o 7 kg.).

Tornando al nostro VISAC, con una spesa aggiuntiva di 30,00 euro si può acquistare l’adattatore dedicato per l’utilizzo di accessori da 2 pollici (già peraltro presente come dotazione standard nell’ultima serie attualmente in commercio).

Il prezzo di 1.670,00 euro, infine, è allineato con quello dei competitor spianati come i Celestron 8” HD (costo di circa 1.650,00 euro) e Meade ACF 8” (listino di 1.700,00 euro) ma risulta molto poco concorrenziale nei confronti degli RC economici della serie GSO che vengono proposti, nel diametro da 20 cm., a poco meno di 1.000,00 euro per la versione in alluminio e 1.530,00 euro per quella in carbonio (ma ad entrambi conviene considerare il minimo upgrade di un focheggiatore migliore).

Non so se sia in assoluto lo strumento migliore (in relazione anche al prezzo) nel panorama dei compound commerciali ma è indubbio che molte delle sue caratteristiche ne fanno un compagno di osservazioni speciale e che la sua messa a punto, pur non semplicissima per via delle molte variabili su cui è possibile intervenire, consente un controllo completo dello strumento e il suo affinamento elevato in grado di trasformarlo in una “lama” affilata, anche a dispetto della importante ostruzione frontale.

Difetti? Difficile trovarne se non la sua attuale livrea (interamente bianca), orribile e molto “cheap”. Notevolmente migliore quella originale (come nell'esemplare del test) con culatta verde “Vixen” che alle qualità intrinseche dello strumento abbina anche un aspetto vagamente professionale. A parte l’aspetto prettamente estetico spiace che Vixen non proponga una versione da 10” a focale compresa tra f8 e f9 che potrebbe essere vincente in un mercato oggi sempre più orientato verso astrografi come gli RC.