MEADE 2045-D

Anno 2019 e 2020

Una modella di oggi posa con uno strumento di ieri.

INTRODUZIONE

Correva l’anno 1993 quando partecipai alla mio primo vero “camping astronomico”, una vacanza di lusso oserei dire di una settimana sulle alpi del Brenta, appena fuori Madonna di Campiglio, ospite della famiglia Maturi che per l’occasione e assecondando la passione in erba del figlio Matteo organizzò “Settimana ad un passo dall’Universo”. Una vacanza full optional alla quale parteciparono anche personaggi di rilievo per l’astronomia italiana come l’amico Walter Ferreri, allora direttore di Nuovo Orione e in forza all’osservatorio di Pino Torinese.

Eravamo tutti giovani, almeno noi ospiti, con tanta passione, entusiasmo e cavalcavamo la linea di confine che diveva la pellicola chimica dai primi ccd della SBIG.

L’importato e distributore Auriga aveva concesso una serie di strumenti in prova per l’occasione e il parco telescopi a disposizione era vasto e anche ben quotato. Avevamo quasi tutti i vari C8 (io un Meade 2080), ma a disposizione cera una delle prime G11 Losmandy (rare da noi) e anche il bellissimo AstroPhysics 130 EDF di Alberto Zinelli e poi anche un sofisticato CN-212 di Giovanni Dal Lago e tanto altro ancora.

Uno dei ragazzi partecipanti si era presentato con un minuscolo Meade 2045 che scimmiottavamo per dimensioni (allora eravamo ancora in preda all’euforia del diametro che vedeva la sua quasi massima aspirazione nel Celestron C11 a disposizione) e il piccolo Schmidt Cassegrain portatile americano ricevette molta poca attenzione.

Oggi, a un quarto di secolo di distanza, dopo aver posseduto tutti i meravigliosi telescopi che allora mi sembravano “il massimo” (e altri ben più prestigiosi e costosi), ricordo con affetto il piccolo table telescopie Meade e in onore di questo malinconico pensiero ho deciso di regalarmene uno.

UN PO' DI STORIA

Il bravo ROD MOLLISE, profondo conoscitore degli Schmidt Cassegrain, oltre al suo blog ha preparato una lunga ricerca sugli SC prodotti al cui interno una manciata di pagine è dedicata anche alla serie "4 pollici" della Meade che, per completezza espositiva, riporto a seguire interamente.

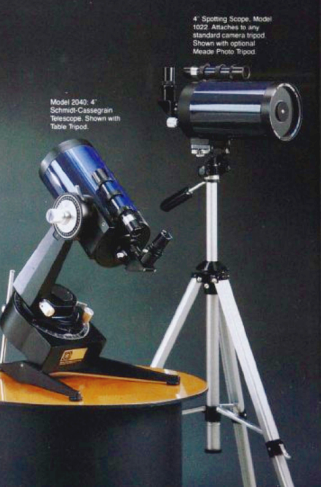

In 1981, only a year after introducing its first SCT, Meade was well on the way to becoming a serious competitor for Celestron. The 2080 had been a pretty sizable hit, and the company quickly rolled out a line of accessories and smaller scopes to reinforce its CAT, referring to the whole shebang as the “Meade System 2000.” One of the elements of this “system” was the incredibly rare Meade Schmidt camera, the 2066 (a 4 inch f/2.54). This thing was of limited appeal, and didn’t hang around too long. The other additions, though, were, in one form or another, to become fixtures in Meade’s stable for many years to come.

Most notable of these was the 2040, a 4-inch SCT. Like Celestron, Meade had a problem: the 8- inch scope, at a thousand dollars with wedge and tripod, seemed nearly as horribly expensive to amateurs of the recession afflicted 80s as the C8 had to the amateurs of the 70s. Celestron tried to address this sticker shock with its C5; now Meade had its own little CAT designed to do the same thing.

Meade’s smaller SCT was “only” a 4- inch, but the 2040 was a pretty little thing with a nice, shiny blue tube. The 2040 was not just a slightly smaller doppelganger of Celestron’s C5, it was considerably different mount-wise, riding on a single-arm fork like the one on the Celestron C90 MCT and the Quantum Maksutovs. As was the case with the later C5+, however, a single tine fork is not necessarily fatal for a small scope. The 2040 was stable, if not solid as a rock on its little mount.

In a marketing strategy identical to the one Celestron used with its C90, the 4- inch OTA was also available in a Spotter

version, the 1022, and as the 1020 Telephoto (no finder, no diagonal), which Meade recommended as a guide-scope for the SCT. That was OK if you didn’t mind lots of trailed stars caused by using one moving-mirror-focusing scope to guide another moving-mirror-focusing scope in the long exposure film days. What’s worth saying about the 2040 in the final analysis? Not too much. It was a competent performer (usually), and the AC spur gear drive was OK. But not many of the 2040s were made before it de-evolved into the almost identical and slightly more numerous and familiar 2044.

When we began to hear that Meade was replacing the 2040 with the “new-improved” 2044, we assumed the scope and mount might be upgraded to something closer to the considerably more expensive and fancy C5 (the 2040 listed for “only” $545.00 in 1981).

However, the 2044 turned out to be not quite what we were expecting. Instead of a “Meade C5,” what we saw, when the Meade full-color ads hit the magazines in 1983, was a 4-inch SCT with an OTA identical to the one on the 2040, but with a considerably lighter and obviously cheapened mount.

The drive base on the 2040 had been similar to the one on the 2080, and the fork arm, while smaller than the arms on the 8-inch scope, was still nice and hefty. The new model’s single fork arm and drive base, however, reminded me more of what had been furnished with Quantum’s super-lightweight scope, the ill-fated Quantum 100. In one fell stroke, all the rumors of an “elegant” Meade 4-inch were stifled.

The 2044, despite my impressions when it was released, is, in retrospect, a nice- looking instrument that’s blessed a certain attractive simplicity and élan. Back in the 80s, though, instead of considering the 2044 to be clean-looking, elegant, or high-tech or thinking “Questar” or “Quantum,” most amateurs just thought the telescope looked cheap. Meade trying to save a few bucks by making the single- arm mount on the 4-inch even lighter, huh?

This small SCT can actually be a very pleasant telescope to use and especially to carry around. Let’s face it, a fully loaded C5 with a field tripod and wedge ain’t that much more portable than a C8. There’s little doubt Meade probably was trying to save a few dollars, but what’s wrong with that? The 2044 was not only cheaper to produce; Meade could sell it for less, still make money, and still deliver a useful scope. The 2044 mounting was fine for visual use, if a little shaky, and was driven by an AC spur-gear more than sufficient for visual use.

How about the optics? To put it plainly, a few 2044s were very good or excellent, most were average, and a few were downright poor. The majority of the 2040/2044 mirror sets I’ve seen over the years tend to be in the “average” category. OK, if nothing to write home about. The 2044’s optical system was usually good enough, but the Meade 4-inch SCT never established a reputation for optical excellence as the C5 had.

Now, Meade was certainly not unaware of the less than stellar reputation its small wonder was earning. Our disdain for the light single-arm fork mounting on the 2044 was quite clear. As a result, the scope was around for barely two years before giving way to an improved 4-inch, the 2045. What can the 2044 (or, maybe even better, the 2040) offer a modern user? Simplicity and portability at a lower price than any vintage of C5. Check the optics, sure, but this is a downright comfortable and friendly little telescope, unarguably better built (metal, metal, metal) than the current ETX Maks. No, the optics ain’t blow-you-away like those on the ETX, but they won’t make you run screaming into the night, either. ‘Course, the catch is, you’re not likely to find a 2040 or a 2044 for sale, as they were made in far smaller numbers than Meade’s “next one,” the ubiquitous 2045. How much do you pay for one? A couple of hundred max is probably fair.

By 1985, Meade’s little CAT, the 2044, was history. It just hadn’t worked out. But was Meade gonna throw in the towel on smaller SCTs? Not hardly. The 2044 was rather quickly replaced by the 2045 and the 2045/LX3.

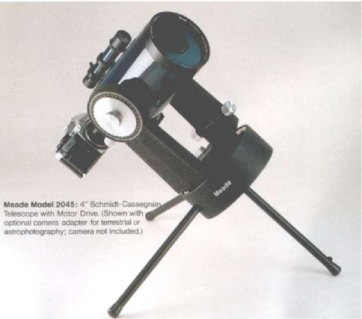

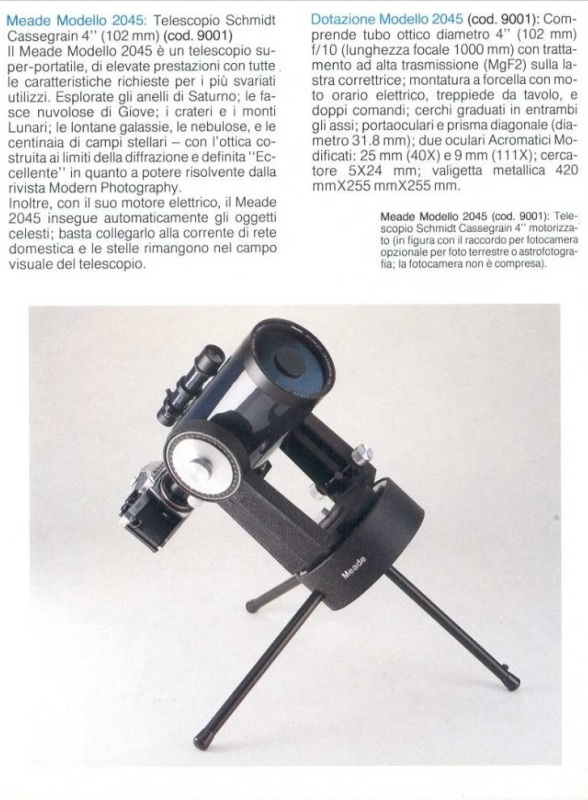

The 2045, the plain vanilla 2045, is much like its ancestor, the 2044: 110V AC spur gear drive, diminutive 5x24mm finder, and three small tabletop legs rather than a real tripod. What made the 2045 different from the 2040/44? The fork, my friends, the fork. Realizing the error of its ways—at least in the eyes of the amateurs of the time—Meade replaced the light single-arm fork of the 2044 with a more normal double tine unit.

The 2045’s support is definitely heavier-duty than the mount on the 2044. The 2045 is actually very much like a 2080 8-inch SCT. As with the C5, it’s as if an 8-inch were left in the dryer too long and shrank. Same RA lock as the 2080. Same declination tangent arm adjustment as the 2080. Same style dual setting circles as the 2080. Same rear port arrangement as the 2080. Same old-fashioned AC drive as the 2080.

There was little, if any, change from the 2044 optics, though. OK images, but not world-beater quality. Meade did make MGF2 coatings on the corrector plate standard on the 2045, though, and they did advertise the telescope as being “diffraction limited.” Unfortunately, that meant about as much back then as it does today—i.e., very little. The coatings did help some. I’ve seen a number of 2045s over the years, and, while I haven’t run across any that were truly horrible, I have yet to find one that I’d describe as “exquisite,” either. Workmanlike? Yes. I’d rate the average C5 as “better”, and not just because of the extra aperture, either (though, as was mentioned earlier, despite the legend that has grown up around the C5, that scope hasn’t always had great optics either).

Should you pony-up for a 2045? Sure, why not? If the price is low enough this makes a good portable scope. The accessories, though not extravagant by 80s standards, are quite nice in today’s reckoning; the scope came with a lovely aluminum carrying case and not one but two eyepieces (albeit simple Kellners, Meade’s Modified Achromats). A prism type star diagonal was standard. Want to do more with your small scope than just look? This 2045 is actually more adaptable for photography than some more modern small CATs. If you can find a drive corrector (for you youngsters, that’s a fancy inverter) and a declination motor to fit the scope, you’re on your way. Of course, if you really want to take pictures with a small scope, you might want to look for one of Meade’s fancy 4-inchers…

“GREAT GOOGLY WOOGLIES!”

That was my reaction, more or less, when I got my first look at Meade’s other 4-inch CAT, the 2045/LX3. This is one fancy puppy...er... “kitty!” It’s furnished with the same fork, drive base and OTA as its more plebian sister, the 2045—it’s what Meade put into that drive base that was so amazing back then. The innovative Meade LX3 quartz DC drive system has been stuffed into this little telescope.

The LX3 can be powered by AC or DC with the appropriate cords, meaning the days of toting around a drive corrector in addition to a battery were over. Photo bug bit? Add the optional #36 hand paddle (which Meade called a “dual-axis controller”) and the #38 declination motor and you were in bidness. ‘Course, if you wanted to take pictures, you’d have to put this little guy on something better than the rinky-dink tabletop legs that shipped with it. But, hey, who was complaining? This was one of the prettiest small CATs ever produced.

So, why aren’t used scope buyers beating the bushes in search of a used LX3 4-inch? A lot of folks today have never even heard of this scope—things change fast in CATdom, and nobody much (except your Old Uncle and a few of his buddies) seems to dwell on the ancient ones. Another reason is that there aren’t that many of these Fancy Dans around. Why? Back in the 80s, this scope’s price was a big problem. At close to 800 smackeroos with no options, you were definitely in C8/2080 territory.

Sure, this was a nice little “portable observatory,” just as the Meade advertisements claimed, but, dollar for dollar, most buyers preferred a bigger—albeit less full-featured—8-inch instead. In other words, the same syndrome that has always been the C5’s downfall. Today, when portable scopes have mucho appeal, the LX3 would no doubt be very popular, but that was not to be back in the day. There never was a 2045/LX5, and the “3” slowly faded away. Optics? Despite multi-coatings on the corrector, a big advance, the 2045/LX3s still were looked upon as somewhat shaky image-wise. I don’t know if this was fair or not, as the few 2045/LX3s I’ve had a chance to use have seemed decidedly better than the base 2045 (though Meade claimed the OTA was the same except for the coatings). I like this little scope, and if one were offered to me, I certainly wouldn’t kick it out of bed for eatin’ crackers!

The 2045 LX3 was attractive and full featured, but by 1990 it was toast. Actually, it didn’t really disappear; it de- evolved, becoming more like its sister, the 2045 standard model. Meade replaced both these telescopes with a new 2045, the “2045D” in late 1990 (although both the 2045 LX3 and 2045 Standard continued to be sold for quite a while, until dealer stocks were exhausted).

De-evolved? In what way? The D’s OTA was the same, featuring Meade’s MCOG (“Multi Coated Optics Group”) SCT optics, but the fancy LX3 drive and hand paddle went bye-bye. The 2045D still has a DC drive (stepper motor) powerable either by AA batteries or a 12v battery via a cigarette lighter cord, but there’s no provision for varying the motor speed for photo guiding. The 2045D’s clock drive is, in fact, much like the drive system on the original ETX, the ETX R.A.—install batteries, switch on, drive runs. The drive’s only feature was the ability to change the direction of drive rotation for Southern Hemisphere operation. A declination motor was available for the D, but without a means of changing the speed of the RA drive for guiding, there wasn’t much point in putting a dec motor on this scope.

The scope has a miniscule 5x24 finder, a diagonal, a 25mm Modified Achromat eyepiece, and a set of three of three silly little table-top legs. Case? You could get one, but it was optional and cost 79 dollars. A field tripod was an available option for $249.00 (wedge included). Which brings us to the matter of the telescope’s price. When it was released, the D cost danged near as much as the 2045 LX3 did—a new D would set you back 800 smackers in 1991. Meade did manage to get the price down after a while, but the high initial pricing may explain why the 2045D never really caught-on with amateurs.

Can I say anything nice about the 2045D? The best part of the scope is its optics. By the time many 2045Ds had gone out the door, Meade, like Celestron, was beginning to pull out of its Halley-generated optics slump. I can tell you that not all 2045Ds are good, but quite a few are very good, noticeably more than was the case with prior Meade 4” SCTs. The fact that the R.A. drive lacks a means of adjusting its speed for guiding is not a big deal. Most people used—and use—these scopes as portable visual instruments, and the fancy LX3 drive was wasted for that reason. All in all, not a half-bad little CAT. It may not have quite lived up to its stated role as an “Eleven and a Half Pound Observatory,” as touted in the Meade ads, but it was and is a pleasing, sturdily constructed little thing. I recommend it. What happened to the 2045D? It hobbled along through 1995 or so (though production may have actually stopped before then). What sunk it? Three letters: E-T-X! In 1996 Meade shifted gears, eliminating its 4 inch SCT and going to a slightly smaller (3.5”) MCT. One with outstanding optics.

None of the several permutations of ETX are as well-built as the 2045s as far as the mount goes, but they are much better optically. So the 2045 is gone forever? Maybe. Maybe not. Meade has recently introduced a pair of sub 8-inch SCTs, the 6-inch Lightswitch and its less fancy sister, the LT, so it’s not out of the bounds of reasonableness to think they might bring out a four to supplement ‘em before all is said and done.

The 2045D is not common on the used market, but neither is it overly rare. A realistic price would be a couple of hundred, plus some more for a scope in outstanding condition, with a nice set of accessories, and a real tripod.

IL RATTO DELLA SABINA

Storicamente, è’ sempre stata Sky & Telescopes ad annunciare le novità del mercato in qualità di rivista ad alta diffusione e riferimento nel modo dell’astronomia amatoriale nell’era pre-web.

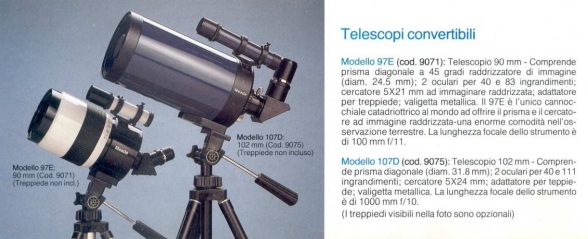

La Criterion propose, in tempi quasi non sospetti, la versione ridotta del Dynamax 8. Il Dynamax 4 apparve nel 1981, in una versione a tre gambette che poi venne ripresa dalla Meade.

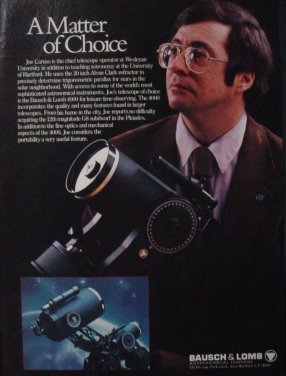

L’anno successivo, il 1982 vide la presentazione del “new Criterion 4000” che venne poi sostituito dal Bausch & Lomb 4000 nella tumultuosa storia Criterion - Bausch & Lomb.

Sebbene Meade avesse fin dal 1981 a catalogo un 4 pollici simile per dimensioni e configurazione, appare evidente che la sua declinazione in “grab & go scope” sia forse da attribuire alla brillante Criterion così come sono ad essa ascrivibili i peggiori errori di assemblaggio che la storia dei telescopi conosca.

Il “Ratto della Sabina” è quindi il modo più simpatico con cui mi sento di descrivere l’invenzione del Meade 2045 che ha, di fatto, mutuato una altrui idea pur realizzandola con modalità superiori e una capacità imprenditoriale ben diversa. Ricordo comunque, su tutto, che la palma del primo design (monobraccio con gambe da tavolo) spetta, fin dal 1954, alla prestigiosa Questar Corporation e alla sua "costola dissidente" OTI (Optical Techniques Inc.) con la serie Quantum.

Sopra: immagine di un Bausch & Lomb 4000 (foto non dell’autore).

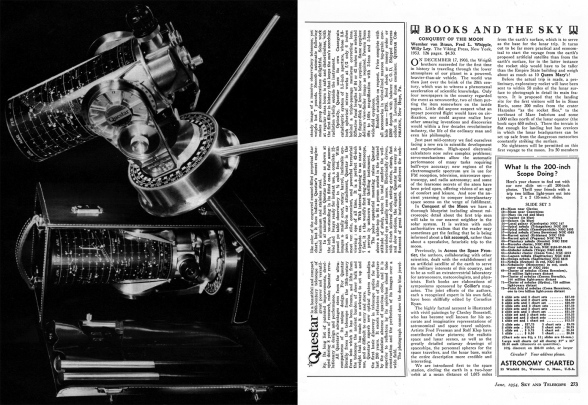

Sotto: June 1954 - la rivista Sky & Telescopes dedica una pagina alla

meravigliosa creatura di Norbert Schell: Il QUESTAR 3,5" (foto non dell'autore).

E’ sempre Sky & Telescopes ad annunciare uno dei più rari strumenti che io conosca, almeno tra quelli “umanamente acquistabili da amatori di medie possibilità economiche, ed è proprio sulle pagine della rivista americana che, nel 1965, compare la pubblicità del Celestron Pacific 4” F25 unobstructed. All’epoca il suo costo non era popolare (quasi il doppio di un 10 pollici Schmidt Cassegrain) ma ancora sostenibile per chi avesse voluto acquistare un piccolo ed improbabile strumento dedicato all’alta risoluzione.

Non ho mai avuto il piacere di vederne uno dal vivo ma forse qualche astrofilo ne possiede ancora uno, magari ricevuto in eredità dal padre. Chiusunque sia lo conservi, lo tenga da conto, ma se proprio non volesse averlo più tra i piedi mi scriva...

RICERCA E ACQUISTO

Avrei voluto recuperare un 2045 serie LX3 poiché, indipendentemente dalle parole di “Uncle Rod”, è quello che esteticamente mi piace di più con il suo pannello multifunzione e la pulsantiera aggiuntiva. Purtroppo la versione LX3 è più rara e quando ho messo annunci di ricerca ho trovato facilmente alcuni 2045 S, D, o precedenti che però versavano in condizioni apparentemente non impeccabili (almeno dal punto di vista cosmetico).

L’amico Giovanni mi ha proposto invece un “D” in condizioni estetiche molto buone (lo strumento appariva “non usato”) ma a sua detta non adeguatamente collimato. La sua ritrosia a lavorarci e l’invito a sistemarlo mi hanno convinto all’acquisto e così il piccolo 2045 è giunto a casa.

Prima di affrontare il nocciolo dell’articolo vorrei spendere alcune parole sulla scelta dello Schmidt Cassegrain (2045) in luogo del Maksutov (ETX) che Rod Mollise indica come otticamente superiore.

Nella mia carriera di astrofilo ho avuto modo di usare e avere alcuni ETX che si sono sempre o quasi rilevati molto ben corretti otticamente e capaci di prestazioni interessanti in relazione al loro diametro.

La lunga focale nativa li rende però a mio avviso meno adatti all’utilizzo “all around” tipico di un piccolo telescopio trasportabile che dovrebbe consentire anche l’osservazione degli oggetti estesi deep sky, possibilmente da cieli bui ad alta quota dove diventa più difficile portare strumenti di diametro cospicuo.

Pur non amando lo schema Schmidt Cassegrain, portare con me in una valigetta un piccolo 10 cm. a f10 molto compatto mi sembra più logico che non scegliere un 9 o 10,5 cm. aperto a quasi f14.

In aggiunta a queste considerazioni il problema degli ETX risiede nelle forcelle e nella meccanica molto più "ballerina" rispetto a quella dei 2045. La continua presenza di vibrazioni che contraddistingue l’osservazione con la serie dei piccoli Maksutov Meade è per me snervante e non la tollero pur apprezzando il moderno sistema goto che li caratterizza.

L’opzione ETX è per me quindi quasi preclusa così come lo è quella QUANTUM o QUESTAR, bellissimi ma troppo costosi per le prestazioni che offrono.

Nelle immagini sopra (non dell'autore) sono ritratti il Meade ETX 90mm. (a sinistra)

e il bellissimo Questar 3,5" (a destra).

PRIMA LUCE

Guardandosi intorno e leggendo sui forum extraoceano (perché è rarissimo trovare informazioni utili sulle piattaforme italiane, solitamente sovrabbondanti di gente che parla senza sapere molto) è possibile recuperare una accettabile quantità di impressioni da parte di utilizzatori che hanno realmente e lungamente convissuto con i loro 2045. La maggior parte delle testimonianze riporta impressioni positive sul piccolo di casa Meade, al tempo stesso sembrano esserci casi di amara delusione. Tra i tanti scritti ne riporto uno che ritengo interessante e utile, pur nella sua laconicità:

“I purchased that little gem second hand on a business trip to Washington D.C. in 2000. Here in Austria, I have enjoyed that telescope for many years now. Being the top of the crop in portability, it is also absolutely convincing by means of optical quality and materials. No plastic will mar your enjoyment, sturdiness is the motto. The "9" for the optics is for the quite tricky alignment of the secondary mirror. To achive the utmost performance, try to get a fitting wood or plexiglass disk with an absolutely centric hole, to be able to center the secondary mirror. The "8" for the Ease of use is mostly for the finder scope. I can hardly manage to get a glimpse through that thing, which comes without a rectangle eyepiece.

Resumee: I have had 5 telescopes, 3 of them are history, the Meade 2045 always will remain at my side.”

In effetti sembra che la qualità delle ottiche e della meccanica di questi strumenti sia buona o molto buona ma che alcuni esemplari (o forse tutti in modo più o meno evidente) soffrano di un assemblaggio non preciso dello specchio secondario e della sua cella. Lo stesso venditore del mio esemplare ha candidamente bollato il 2045 ora nelle mie mani come "un fondo di bottiglia tanto che un banale rifrattore 70/500 acromatico cinese ne fa polpette in un confronto diretto". Con questa inquietante premessa mi sono dedicato alla "prima luce" dello strumento senza pulire, collimare, testare in altro modo il telescopio.

Il primo responso sul cielo è stato inclemente. L’apparenza era quella di una ottica ben lavorata, appena fuori “asse”, ma il solo tentativo di collimazione ha mandato tutto a rotoli.

La cella porta secondario ha cominciato a ruotare nella propria sede rendendo impossibile qualsiasi tipo di intervento.

I centri ottici sono andati a farsi benedire, l’immagine è passata da “quai accettabile” a “inguardabile”, e l’intera lastra di Schmidt ha dimostrato di saper ballare la “tarantella” nella sua sede.

Davanti a tanto disastro non ho potuto che rincasare con lo strumento e operare una primo disassemblaggio per comprendere cosa ci fosse di non correttamente montato.

Purtroppo mi trovavo in montagna, con pochi strumenti a disposizione, e così ho potuto fare poco, obbligandomi ad attendere il ritorno a Milano.

SISTEMAZIONE DELLO STRUMENTO

La calma degli ultimi scampoli di vacanza natalizia mi hanno permesso, una volta in città, di porre mano all’ottica del portatile americano che appariva soffrire di una serie di problematiche legate all’inadeguato posizionamento dei suoi elementi ottici nonché ad un non felice assemblaggio originale.

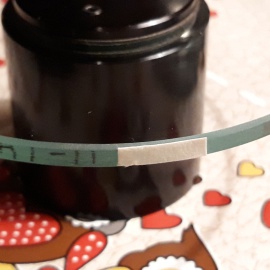

Poiché lo strumento nasce con il suo diagonale prismatico in tutt’uno con la ghiera filettata di collegamento alla culatta mi sono preoccupato di capire se l’asse del prisma diagonale coincidesse con quello dell’ottica principale.

Poiché così non appariva ho dovuto smontare il prisma e rimontarlo con i corretti spessori di frizione in modo da eliminare una delle incognite nell’equazione della corretta collimazione.

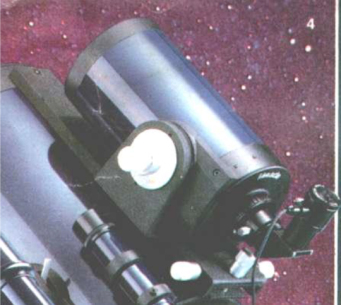

E’ poi venuto il turno della lastra correttrice e della sua giusta rotazione e posizione in relazione alla cella porta ottica.

Anche il sistema di ritenzione del secondario, comune a tutti o quasi gli Schmidt Cassegrain dell’epoca e privo di molle reggispinta, non aiuta la gestione del complesso ottico anteriore ma dopo un paio d’ore di lavoro ho finalmente raggiunto una immagine correttamente rotonda sia del riflesso del primario che del secondario ed anche una accettabile allineamento del diagonale.

Era ora di collimare, operazione eseguita sulla brillante Capella, e di godere finalmente delle qualità di lavorazione degli specchi.

L’immagine della fulgida Alpha Aurigae appariva contrastata e molto ben puntiforme, con un primo anello di diffrazione leggibile, anche al potere di 150x circa offerti dal plossl 3000 da 6,7 millimetri.

Sopra e sotto: vista frontale della lastra di Schmidt e vista laterale dello strumento (senza piedi)

OSSERVAZIONE DEEP SKY

Ci sono astrofili che ritengono 10 cm. inutili nell’osservazione del cielo profondo e benché non si possa affermare che 4 pollici siano tanti va anche ammesso che, sotto cieli davvero bui, anche i 102 millimetri ostruiti del Meade 2045 hanno saputo farsi apprezzare.

La visione del doppio ammasso del Perseo, in unione all’oculare SWA da 24,5 millimetri (che permette un potere di 41x e un campo reale superiore ai 1,6°) si mostra convincente. La puntiformità stellare e la saturazione dei colori assicurano una bella immagine anche se le componenti più deboli degli ammassi restano quasi al limite della percezione. In questo caso un rifrattore da 15 cm. offre un guadagno incredibile ma richiede anche ingombri e montature di classe elevata.

Lo strumento mi ha invece stupito molto su altri soggetti come la coppia di galassie M81 e M82 capaci di mostrarsi con una grande quantità di dettagli (accenno di bracci per M81 e una serie di nodosità e chiaro/scuri lungo il fuso di M82). L’immagine delle due galassie insieme sul cielo buio è sempre molto bello ma osservarle singolaremente, con un potere maggiore e prossimo ai 67x dell’oculare da 15 mm. e ai 72 x (SWA da 13,8mm.) consente di fare emergere il massimo dei dettagli alla portata del telescopio e del cielo.

Indagare le plaghe centrali della costellazione di Orione, che si ergeva sulle vette innevate delle Alpi, ha permesso di cogliere (oculare plossl da 25 mm.) la diafana ma ben strutturata FLAME NEBULA che mostrava, pur con la brillante Alnitak nel campo, almeno 3 rami principali e una serie di indentature. Debole e fumosa, ma inequivocabile nelle sue features, la FLAME si è prestata ad un confronto diretto tra il 2045 catadiottrico e il rifrattore apo Meade da 10 cm. (il vecchio e glorioso 102ED EMC f9).

Nonostante la superiorità ottica globale del rifrattore apocromatico la differenza all’atto pratico nella percezione dei dettagli deboli si è mostrata limitata.

Il rifrattore, grazie alla mancanza di ostruzione, ha ovviamente permesso una maggiore godibilità della nebulosa ma i dettagli e i canali visibili sono pressoché identici anche se il rifrattore li rende più “densi”.

La medesima differenza è emersa nell’osservazione della grande nebulosa di Orione M42 con le sue volute verde-grigio. La densità della nebulosa, molto maggiore di quanto permesso dalla “fiamma” si è mostrata in volute stratificate con un contrasto notevole in entrambi gli strumenti.

Anche in questo caso il rifrattore apocromatico ha mostrato una leggera superiorità sia per quanto riguarda il contrasto che la percezione delle propaggini più deboli della nebulosa. In entrambi gli strumenti le stelle del trapezio si sono mostrate sottili e ben definite, indipendentemente dall’ingrandimento usato (e questo anche in virtù di una nottata con condizioni di seeing buone, cosa rara dai passi alpini).

La pazienza di attendere il cuore della notte, pur con il pungente freddo dei 1800 metri di quota, mi ha permesso di scendere fino alla Poppa e al suo bellissimo ammasso aperto M46, ricchissimo di stelle colorate e sottili. Sia il 102 ostruito che il rifrattore apo mi hanno ovviamente mostrato molto bene l’ammasso ma non posso che consegnare la palma del vincitore al rifrattore per la densità cromatica concessa e per la maggiore e generale pulizia di immagine. Nonostante questo devo anche ammettere che le differenze mi sono apparse piuttosto contenute.

Entrambi i telescopi mi hanno dato accesso alla peculiare planetaria NGC 2438, visibile come un anellino denso e luminoso posto nelle zone periferiche dell’ammasso aperto che nel rifrattore è apparsa appena più convincente.

Non ho ovviamente dimenticato alcuni soggetti altrettanto facili e famosi, comodi anche perché molto alti sull’orizzonte: l’ammasso M45 delle Pleiadi e la piccola ma luminosa M1.

Le sorelle celesti si sono mostrate bene anche se non hanno permesso di cogliere, almeno in visuale, tracce significative della nebulosità bluastra in cui sono immerse. La Nebulosa del Granchio invece ha ben evidenziato la sua forma ellissoidale non simmetrica con un accenno di gradiente ma nessun ulteriore dettaglio significativo.

Il maggiore campo spianato del rifrattore si è fatto molto apprezzare nella visione di M45 dove il Meade catadiottrico ha patito un po’ la sua curvatura di campo e il coma non corretto.

Entrambi gli strumenti mi hanno anche permesso di indagare il centinaio di stelle di M35, nei piedi dei Gemelli, mentre non ho avuto sentore del lontano 2158, se non forse in visione distolta con il rifrattore apo.

UTILIZZO NEL TEMPO: PROBLEMI OTTICO-MECCANICI

Una volta riposto nel suo bauletto, lo strumento ha sonnecchiato qualche mese prima di essere nuovamente impiegato.

Riportare sotto le stelle il Meade 2045 ha riportato in auge anche i problemi che sembravano risolti dal primo intervento di collimazione.

La meccanica non ha semplicemente “tenuto” palesando nuove aberrazioni geometriche importanti, tra cui un inspiegabile disassamento del secondario all’interno dell’asola della lastra di Schmidt.

In linea del tutto teorica mi spiego benissimo il problema ma mi ha creato notevole scoramento constatarlo nuovamente e dover accettare il fatto che lo strumento avesse bisogno di nuove cure.

Dopo una notte di tribolazioni ho così deciso di “abbandonare” il progetto Meade 2045 dopo aver sistemato accettabilmente bene le ottiche e stabilito che, in fin dei conti, il numero sproporzionato di telescopi a mia disposizione non richiedesse l’aiuto ulteriore di un piccolo S-C da 10 cm. in configurazione miniaturizzata.

Ho così destinato il bel 2045-D al rango di soprammobile nel mio studio tecnico in sala riunioni.

Per chi invece decide diversamente e desidera che il suo 2045 sia compagno di viaggio e di osservazioni si apre una lunga opera di rifacimento di alcune parti fondamentali dello strumento compresa, a mio avviso, la modifica della sede dello specchio secondario affinché il “gioco” interno all’assale della lastra correttrice, sia più limitato.

Indipendentemente dalle prestazioni ottiche pure che, una volta che il telescopio è “a posto” sono più che soddisfacenti come abbiamo visto emergere del test, il 2045, così come il suo successore ETX ma anche così come avviene per i vari B%L 4000 o per i rinomati Questar, offre un problema di fondo che personalmente me lo fa relegare a oggetto da mobilio più che da vero telescopio “under the stars”.

La sua “miniaturizazione” impone che tutto sia compattissimo, vicino, molto difficilmente gestibile in modo tradizionale. Osservare con questi piccoli catadiottri è esperienza un po’ ridicola, soprattutto se si è abituati a strumenti più grandi.

Sembra un poco di mangiare in un piatto piccolo con grandi bacchette cinesi che stanno sempre un po’ tra “i piedi”.

Diventa difficile trovare ad esempio un piano adatto ad installare il telescopio con le sue gambette vanificando così nella pratica una idea che sulla carta appare intelligente.

La piccola dimensione della manopola di messa a fuoco nonché la enorme difficoltà di puntare gli oggetti stellari usando i moti manuali e cercando di traguardare attraverso il cercatore o qualche punto di allineamento del tubo ottico tendono a “scoraggiare” anche osservatori esperti.

Si perde, insomma, la logica dello strumento “mordi e fuggi” e ci si impantana in un impiego delicato e fatto di spostamenti micrometrici certosini che male si addicono alla logica dell’insieme.

CONCLUSIONI

Il 2045 Meade è uno strumento a mio modo di vedere tanto bello quanto poco utile.

Esattamente come avviene per altri micro-telescopi non computerizzati (mi riferisco ai B&L 4000 o ai costosissimi Questar da 3,5") l’impiego migliore che l’astrofilo evoluto può loro dedicare è quello di oggetto decorativo.

Non mi sento di consigliarne l'acquisto se ciò che si cerca è un telescopio da portarsi in aereo. Per questo, non vi è alcun dubbio, si deve rivolgere la propria attenzione ai più moderni ETX goto oppure ad altre configurazioni alternative come i Vixen VMC gestiti da piccole montature a palmare. Oramai l’era dei contorsionismi manuali è finita e non ha davvero senso tentare di tenerla in vita per semplice amore nostalgico.

Tralasciate le personalissime valutazioni di fruibilità vanno considerati anche i difetti meccanici che, pur risolvibili, richiedono interventi attenti e magari anche costosi che possono scoraggiare la maggior parte degli interessati.

Pur con tutte queste pecche il 2045 resta uno strumento che il grande appassionato può avere, anche solo per il piacere di possedere un piccolo telescopio completo il cui valore può oscillare tra i 250 e i 400 euro a seconda della versione e dello stato cosmetico e di completezza in cui si presenta. Se però volete osservare meglio che acquistiate un "80-ED" qualsiasi su una montatura equatoriale decente.